Crossparty work yet to do on the Online Safety Bill

Finally the Online Safety Bill has arrived in the House of Lords. This is what I said on winding up at the end of the debate which had 66 speakers in total, many of them making passionate and moving speeches. We all want to see this go through, in particular to ensure that children and vulnerable adults are properly protected on social media, but there are still changes we want to see before it comes into law.

My Lords, I thank the Minister for his detailed introduction and his considerable engagement on the Bill to date. This has been a comprehensive, heartfelt and moving debate, with a great deal of cross-party agreement about how we must regulate social media going forward. With 66 speakers, however, I sadly will not be able to mention many significant contributors by name.

It has been a long and winding road to get to this point, as noble Lords have pointed out. As the Minister pointed out, along with a number of other noble Lords today, I sat on the Joint Committee which reported as far back as December 2021. I share the disappointment of many that we are not further along with the Bill. It is still a huge matter of regret that the Government chose not to implement Part 3 of the DEA in 2019. Not only, as mentioned by many, have we had a cavalcade of five Culture Secretaries, we have diverged a long way from the 2019 White Paper with its concept of the overarching duty of care. I share the regret that the Government have chosen to inflict last-minute radical surgery on the Bill to satisfy the, in my view, unjustified concerns of a very small number in their own party.

Ian Russell—I pay tribute to him, like other noble Lords—and the Samaritans are right that this is a major watering down of the Bill. Mr Russell showed us just this week how Molly had received thousands and thousands of posts, driven at her by the tech firms’ algorithms, which were harmful but would still be classed as legal. The noble Lord, Lord Russell, graphically described some of that material. As he said, if the regulator does not have powers around that content, there will be more tragedies like Molly’s.

The case for proper regulation of harms on social media was made eloquently to us in the Joint Committee by Ian and by witnesses such Edleen John of the FA and Frances Haugen, the Facebook whistleblower. The introduction to our report makes it clear that the key issue is the business model of the platforms, as described by the noble Lords, Lord Knight and Lord Mitchell, and the behaviour of their algorithms, which personalise and can amplify harmful content. A long line of reports by Select Committees and all-party groups have rightly concluded that regulation is absolutely necessary given the failure of the platforms even today to address these systemic issues. I am afraid I do not agree with the noble Baroness, Lady Bennett; being a digital native is absolutely no protection—if indeed there is such a thing as a digital native.

We will be examining the Bill and amendments proposed to it in a cross-party spirit of constructive criticism on these Benches. I hope the Government will respond likewise. The tests we will apply include: effective protections for children and vulnerable adults; transparency of systems and power for Ofcom to get to grips with the algorithms underlying them; that regulation is practical and privacy protecting; that online behaviour is treated on all fours with offline; and that there is a limitation of powers of the Secretary of State. We recognise the theme which has come through very strongly today: the importance of media literacy.

Given that there is, as a result of the changes to the Bill, increased emphasis on illegal content, we welcome the new offences, recommended in the main by the Law Commission, such as hate and communication crimes. We welcome Zach’s law, against sending flashing images or “epilepsy trolling”, as it is called, campaigned for by the Epilepsy Society, which is now in Clause 164 of the Bill. We welcome too the proposal to make an offence of encouraging self-harm. I hope that more is to come along the lines requested by my noble friend Lady Parminter.

There are many other forms of behaviour which are not and will not be illegal, and which may, according to terms of service, be entirely legal, but are in fact harmful. The terms of service of a platform acquire great importance as a result of these changes. Without “legal but harmful” regulation, platforms’ terms of service may not reflect the risks to adults on that service, and I was delighted to hear what the noble Baroness, Lady Stowell, had to say on this. That is why there must be a duty on platforms to undertake and publish risk and impact assessments on the outcomes of their terms of service and the use of their user empowerment tools, so that Ofcom can clearly evaluate the impact of their design and insist on changes or adherence to terms of service, issue revised codes or argue for more powers as necessary, for all the reasons set out by the noble Baroness, Lady Gohir, and my noble friend Lady Parminter.

The provisions around user empowerment tools have now become of the utmost importance as a result of these changes. However, as Carnegie, the Antisemitism Policy Trust, and many noble Lords today have said, these should be on by default to protect those suffering from poor mental health or who might lack faculty to turn them on.

Time is short today, so I can give only a snapshot of where else we on these Benches—and those on others, I hope—will be focusing in Committee. The current wording around “content of democratic importance” and “journalistic content” creates a lack of clarity for moderation processes. As recommended by the Joint Committee, these definitions should be replaced with a single statutory requirement to protect content where there are reasonable grounds to believe it will be in the public interest, as supported by the Equality and Human Rights Commission.

There has been a considerable amount of focus on children today, and there are a number of amendments that have clearly gained a huge amount of support around the House, and from the Children’s Charities’ Coalition on Internet Safety. They were so well articulated by the noble Baroness, Lady Kidron. I will not adumbrate them, but they include that children’s harms should be specified in the Bill, that we should include reference to the UN convention, and that there should be provisions to prevent online grooming. Particularly in the light of what we heard this week, we absolutely support those campaigning to ensure that the Bill provides for coroners to have access to children’s social media accounts after their deaths. We want to see Minister Scully’s promise to look at this translate into a firm government amendment.

We also need to expressly future-proof the Bill. It is not at all clear whether the Bill will be adequate to regulate and keep safe children in the metaverse. One has only to read the recent Institution of Engineering and Technology report, Safeguarding the Metaverse, and the report of the online CSA covert intelligence team, to realise that it is a real problem. We really need to make sure that we get the Bill right from this point of view.

As far as pornography is concerned, if we needed any more convincing of the issues surrounding children’s access to pornography, the recent research by the Children’s Commissioner, mentioned by several noble Lords, is the absolute clincher. It underlines the importance of the concerns of the coalition of charities, the noble Lord, Lord Bethell, and many other speakers today, who believe that the Online Safety Bill does not go far enough to prevent children accessing harmful pornographic content. We look forward to debating those amendments when they are put forward by the noble Lord, Lord Bethell.

We need to move swiftly on Part 5 in particular. The call to have a clear time limit to bring it in within six months of the Bill becoming law is an absolutely reasonable and essential demand.

We need to enshrine age-assurance principles in the Bill. The Minister is very well aware of issues relating to the Secretary of State’s powers. They have been mentioned by a number of noble Lords, and we need to get them right. Some can be mitigated by further and better parliamentary scrutiny, but many should simply be omitted from the Bill.

As has been mentioned by a number of noble Lords, there is huge regret around media literacy. We need to ensure that there is a whole-of-government approach to media literacy, with specific objectives set for not only Ofcom but the Government itself. I am sure that the noble Lord, Lord Stevenson, will be talking about an independent ombudsman.

End-to-end encryption has also come up; of course, that needs protecting. Clause 110 on the requirement by Ofcom to use accredited technology could lead to a requirement for continual surveillance. We need to correct that as well.

There is a lot in the Bill. We need to debate and tackle the issue of misinformation in due course, but this may not be the Bill for it. There are issues around what we know about the solutions to misinformation and disinformation and the operation of algorithmic amplification.

The code for violence against women and girls has been mentioned. I look forward to debating that and making sure that Ofcom has the power and the duty to produce a code which will protect women and girls against that kind of abuse online. We will no doubt consider criminal sanctions against senior managers as well. A Joint Committee, modelled on the Joint Committee on Human Rights, to ensure that the Bill is future-proofed along the lines that the noble Lords, Lord Inglewood and Lord Balfe, talked about is highly desirable.

The Minister was very clear in his opening remarks about what amendments he intends to table in Committee. I hope that he has others under consideration and that he will be in listening mode with regard to the changes that the House has said it wants to see today. Subject to getting the Bill in the right shape, these Benches are very keen to see early implementation of its provisions.

I hope that the Ofcom implementation road map will be revised, and that the Minister can say something about that. It is clearly the desire of noble Lords all around the House to improve the Bill, but we also want to see it safely through the House so that the long-delayed implementation can start.

This Bill is almost certainly not going to be the last word on the subject, as the noble Baroness, Lady Merron, very clearly said at the beginning of this debate, but it is a vital start. I am glad to say that today we have started in a very effective way.

Tackling the Harms in the Metaverse

I recentlty took part in a session entitled Regulation and Policing of Harm in the Metaverse as part of a Society for Computers and the Law and Queen Mary University of London policy forum on the metaverse alongside Benson Egwuonwu from DAC Beechcroft and Professor Julia Hornle Chair of Internet Law at the Centre for Commercial Law Studies at Queen Mary

This is what i said in my introduction.

This is what two recent adverts from Meta said:

- “In the metaverse farmers will optimize crop yields with real time data”

- “In the metaverse students will learn astronomy by orbiting Saturn’s rings”

Both end with the message “The metaverse may be virtual but the impact is real”.

This is an important message but the first advert is a rather baffling use of the metaverse, the second could be quite exciting. Both adverts are designed to make us think about the opportunities presented by it.

But as we all know, alongside the opportunities there are always risks. It is very true of Artificial Intelligence, a subject I speak on regularly, but particularly as regards the metaverse.

The metaverse opens new forms and means of visualisation and communication but I don’t believe that there is yet a proper recognition that the metaverse in the form of immersive games which use avatars and metaverse chat rooms can cause harm or of the potential extent of that harm.

I suspect this could be because although we now recognize that there are harms in the Online world, the virtual world is even further away from reality and we again have a pattern repeating itself. At first we don’t recognize the potential harms that a new and developing technology such as this presents until confronted with the stark consequences.

The example of the tragic death of Molly Russell in relation to the understanding of harm on social media springs to mind

So in the face of that lack of recognition it’s really important to understand the nature of this potential harm, how can it be addressed and prevent what might become the normalisation of harm in the metaverse

The Sunday Times in a piece earlier this year on Metaverse Harms rather luridly headlined “My journey into the metaverse — already a home to sex predators” asserted: “....academics, VR experts and children’s charities say it is already a poorly regulated “Wild West” and “a tragedy waiting to happen” with legislation and safeguards woefully behind the technology. It is a place where adults and children, using their real voices, are able to mingle freely and chat, their headsets obscuring their activities from those around them.”

It went on: “Its immersive nature makes children particularly vulnerable, according to the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) charity.”

This is supported by the Center for Countering Digital Hate’s investigation last year into Facebook’s VR metaverse which found children exposed to sexual content, bullying and threats of violence.

And there are other potential and actual harms too not involving children. Women and girls report being harassed and sexually assaulted, there is also fraudulent activity and racial abuse.

It is clear that because of the very nature of the metaverse- the impact of its hyper-realistic environment -there are specific and distinct harms the metaverse can cause that are different from other online platforms.

These include harms that may as yet be unquantified – which makes regulation difficult. There is insufficient knowledge and understanding about harms such as the potentially addictive impact of the metaverse & other behavioural and cognitive effects it may have.

Policy and enforcement are made more difficult by fact that the metaverse is intended to allow real-time conversations. Inadequate data storage of activity on the metaverse could mean a lack of evidence to prove harm and the track of perpetrators but in turn this also raises conflicting privacy questions.

So What does the Online Safety Bill do?

It is important that metaverse is included within the platform responsibilities proposed by the bill. The Focus of the bill is about systems and risk assessment relating to published content but metaverse platforms are about activity happening in real-time and we need to appreciate and deal with this difference. It also shows the importance of having a future proofing mechanism within the bill but one that is not reliant on the decision of the Secretary of State for Culture Media and Sport.

There is the question whether the metaverse definition of regulated services currently falls within scope. This was raised by my colleagues in the Commons and ministerial reassurance was given in relation to childrten but we have had two Ministerial changes since then!

Architects of the Bill such as CarnegieUK are optimistic that the metaverse – and the tech companies who create it will not escape regulation in the UK because of the way that user generated content is defined in clause 50 and the reference there to “encountered”.

It is very likely that harms to children in the metaverse on these services will be caught.

As regards adults however the OSB now very much focuses on harmful illegal content. Query whether it will or should capture analogous crimes within the metaverse so for instance is ‘virtual rape and sexual assault’ considered criminal in the metaverse?

As regards content outside this, the current changes which have been announced to the bill which focus on Terms of Service rather than ‘legal but harmful’ create uncertainty.

It seems the idea is to give power to users to exclude other participants who are causing or threantening but how is this practical in the context of the virtual reality of the metaverse?

A better approach might be to clearly regulate to drive Safety by Design. Given the difficulties which will be encountered in policing and enforcement I believe the emphasis needs to be placed on design of metaverse platforms and consider at the very outset how platform design contributes to harm or delivers safety.

Furthermore at present there is no proper independent complaints or redress mechanism such as an Ombudsman proposed for any of these platforms which in the view of many is a gaping hole in the governance of social media which includes the metaverse.

In a recent report The Center for Countering Digital Hate recorded 100 potential violations of Meta’s policies in 11 hours on Facebook’s VR chat . CCDH researchers found that users, including minors, are exposed to abusive behaviour every seven minutes. Yet the evidence is also that Meta is already unresponsive to reports of abuse. It seems that of those 100 potential violations, only 51 met Facebook’s criteria for reporting offending content, as the platform rejects reports if it cannot match them to a username in its database.

Well we are expecting the Bill in the Lords in the early New Year . We’ll see what we can do to improve it!

Lord C-J at the Piccaso Data Privacy Awards

I recently attended and spoke at the inaugural Piccaso Data Privacy awards celebrating the contribution of businessers and organisations innovating in data privacy .

Piccaso is an acronym (Privacy, InfoSec, Culture, Change , Awareness, Societal Organisation) for an organisation which aims to harness "the knowledge and experience of experts both from the privacy, data protection, and information security domains to inspire, challenge, and educate our community to elevate the practice of privacy and data protection maturity within their firms and sectors."

This is what I said.

I’m delighted to have been asked to make a few remarks at this evening’s terrific inaugural Piccasso event… and it’s a privilege to follow the avatar of John Edwards the Information Commissioner, especially his sales pitch for the ICO! It is a great example of his positive approach to regulation which we know needs to be principled, proportionate and communicative.

Continuing the wise approach of his predecessor, Elizabeth Denham who I am delighted to see is one of our judges.

We of course have new data protection legislation coming down the track which may or may not prove positive, which we are going to have to grapple with inside and outside Parliament fairly soon

I hope that whatever changes are made to the GDPR its broad approach will continue, and any changes to the GDPR structure and oversight of the regulator, mean we not only remain data adequate for EU purposes but keep public trust in the use and sharing of their data in the UK!

And the need for public trust in the use and sharing of our data and the preservation of individual privacy is crucial if we are to get the full benefit of the adoption of new technologies such as AI and Machine learning. We have seen how when trust fails, such as with the poorly handled GP data saga last year, when over three million NHS patients opted out of sharing their health data.

This is a unique and very special event gathering together the full width of community, public and private and third sector, who really get this and each of whom is supporting privacy compliant innovation, by developing privacy enabling solutions, ensuring organisations use their data in a privacy by design and trusted way, and enabling individuals to exercise their privacy rights.

The 15 award categories tonight and those people and organisations nominated give a real sense of the breadth of the skills and talent present – all of you focussed on making our organisations, economy and society a trusted and safe place to live and operate.

Tonight’s event is a celebration of your incredible contributions, which are all too often overlooked and under-appreciated.

Given that a culture of privacy protection is not always the rule, I want us to commend and celebrate the good work that is being done by so many in this room tonight - including those engaged in thought leadership, testing and setting boundaries and devising creative policy approaches which address new developments such as blockchain, Web 3.0 and the Metaverse.

You all know, live with and understand the importance of data protection and privacy, and your leadership is helping to enable a safer future, and one where innovation is encouraged.

So whether you win or not tonight, thank you - and congratulations for playing a really important role in a privacy protecting future!

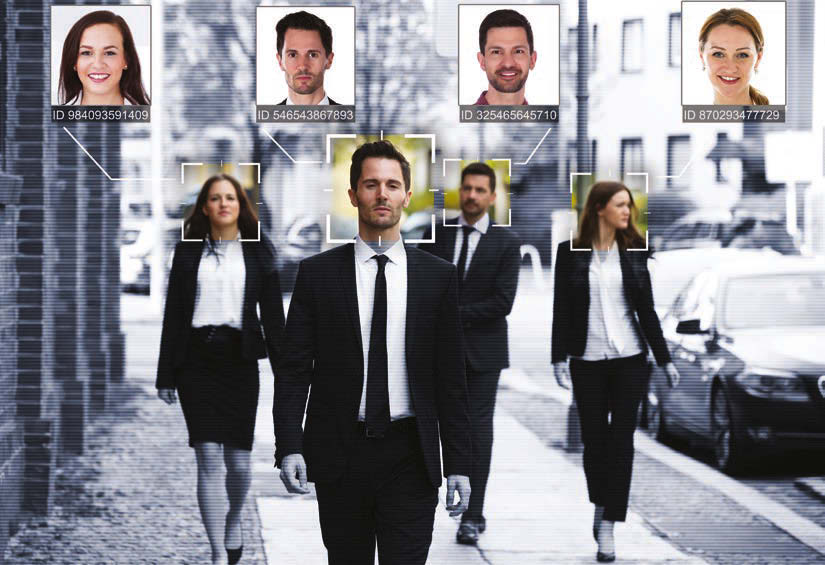

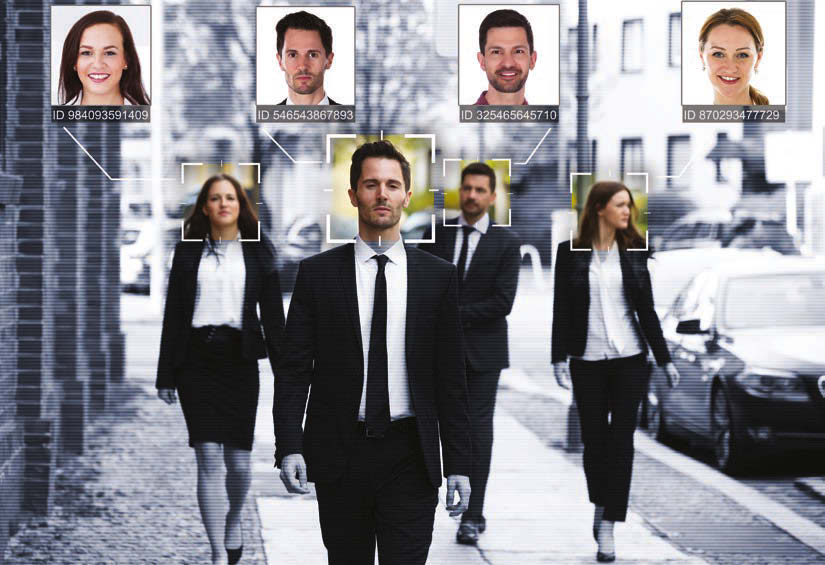

It's time to have a moratorium on Live Facial Recognition use

We recently debated the recommendations of the Lords Justice and Home Affairs Committee Report Technology rules? The advent of new technologies in the justice system

This is what I said on welcoming the $eport.

I entirely understand and welcome the width of the report but today I shall focus on live facial recognition technology, a subject that I have raised many times in this House and elsewhere in Questions and debates, and even in a Private Member’s Bill, over the last five years. The previous debate involving a Home Office Minister—the predecessor of the noble Lord, Lord Sharpe, the noble Baroness, Lady Williams—was in April, on the new College of Policing guidance on live facial recognition.

On each occasion, I drew attention to why guidance or codes are regarded as insufficient by myself and many other organisations such as Liberty, Big Brother Watch, the Ada Lovelace Institute, the former Information Commissioner, current and former Biometrics and Surveillance Camera Commissioners and the Home Office’s own Biometrics and Forensics Ethics Group, not to mention the Commons Science and Technology Committee. On each occasion, I have raised the lack of a legal basis for the use of this technology—and on each occasion, government Ministers have denied that new explicit legislation or regulation is needed, as they have in the wholly inadequate response to this report.

In the successful appeal of Liberal Democrat Councillor Ed Bridges, the Court of Appeal case on the police use of live facial recognition issued in August 2020, the court ruled that South Wales Police’s use of such technology had not been in accordance with the

law on several grounds, including in relation to certain human rights convention rights, data protection legislation and the public sector equality duty. So it was with considerable pleasure that I read the Justice and Home Affairs Committee report, which noted the complicated institutional landscape around the adoption of this kind of technology, emphasised the need for public trust and recommended a stronger legal framework with primary legislation embodying general principles supported by detailed regulation, a single national regulatory body, minimum scientific standards, and local or regional ethics committees put on a statutory basis.

Despite what paragraph 4 of the response says, neither House of Parliament has ever adequately considered or rigorously scrutinised automated facial recognition technology. We remain in the precarious position of police forces dictating the debate, taking it firmly out of the hands of elected parliamentarians and instead—as with the recent College of Policing guidance—marking their own homework. A range of studies have shown that facial recognition technology disproportionately misidentifies women and BAME people, meaning that people from those groups are more likely to be wrongly stopped and questioned by police, and to have their images retained as the result of a false match.

The response urges us to be more positive about the use of new technology, but the UK is now the most camera-surveilled country in the Western world. London remains the third most surveilled city in the world, with 73 surveillance cameras for every 1,000 people. The last Surveillance Camera Commissioner did a survey, shortly before stepping down, and found that there are over 6,000 systems and 80,000 cameras in operation in England and Wales across 183 local authorities. The ubiquity of surveillance cameras, which can be retrofitted with facial recognition software and fed into police databases, means that there is already an apparatus in place for large-scale intrusive surveillance, which could easily be augmented by the widespread adoption of facial recognition technology. Indeed, many surveillance cameras in the UK already have advanced capabilities such as biometric identification, behavioural analysis, anomaly detection, item/clothing recognition, vehicle recognition and profiling.

The breadth of public concern around this issue is growing clearer by the day. Many cities in the US have banned the use of facial recognition, while the European Parliament has called for a ban on the police use of facial recognition technology in public places and predictive policing. In 2020 Microsoft, IBM and Amazon announced that they would cease selling facial recognition technology to US law enforcement bodies.

Public trust is crucial. Sadly, the new Data Protection and Digital Information Bill does not help. As the Surveillance Camera Commissioner said last year, in a blog about the consultation leading up to it:

“This consultation ought to have provided a rare opportunity to pause and consider the real issues that we talk about when we talk about accountable police use of biometrics and surveillance, a chance to design a legal framework that is a planned response to identified requirements rather than a retrospective reaction to highlighted shortcomings, but it is an opportunity missed.”

Now we see that the role of Surveillance Camera Commissioner is to be abolished in the new data protection Bill—talk about shooting the messenger. The much-respected Ada Lovelace Institute has called, in its report Countermeasures and the associated Ryder review in June this year, for new primary legislation to govern the use of biometric technologies by both public and private actors, for a new oversight body and for a moratorium until comprehensive legislation is passed.

The Justice and Home Affairs Committee stopped short of recommending a moratorium on the use of LFR, but I agree with the institute that a moratorium is a vital first step. We need to put a stop to this unregulated invasion of our privacy and have a careful review, so that its use can be paused while a proper regulatory framework is put in place. Rather than update and use toothless codes of practice, as we are urged to do by the Government, to legitimise the use of new technologies such as live facial recognition, the UK should have a root-and-branch surveillance camera and biometrics review, which seeks to increase accountability and protect fundamental rights. The committee’s report is extremely authoritative in this respect. I hope today that the Government will listen but, so far, I am not filled with optimism about their approach to AI governance.

AI Governance: Science and Technology Committee launches enquiry

The House of Commons Science and Technology Committee has launched an inquiry into the governance of artificial intelligence (AI).

This is what they said on launching it:

In July, the UK Government set out its emerging thinking on how it would regulate the use of AI. It is expected to publish proposals in a White Paper later this year, which the Committee would examine in its inquiry.

Used to spot patterns in large datasets, make predictions, and automate processes, AI’s role in the UK economy and society is growing. However, there are concerns around its use. MPs will examine the potential impacts of biased algorithms in the public and private sectors. A lack of transparency on how AI is applied and how automated decisions can be challenged will also be investigated.

In the inquiry, MPs will explore how risks posed to the public by the improper use of AI should be addressed, and how the Government can ensure AI is used in an ethical and responsible way. The Committee seeks evidence on the current governance of AI, whether the Government’s proposed approach is the right one, and how their plans compare with other countries.

Rt Hon Greg Clark MP, Chair of Science and Technology Committee, said:

“AI is already transforming almost every area of research and business. It has extraordinary potential but there are concerns about how the existing regulatory system is suited to a world of AI.

With machines making more and more decisions that impact people’s lives, it is crucial we have effective regulation in place. In our inquiry we look forward to examining the Government’s proposals in detail.”

These are these key questions they are asking

- How effective is current governance of AI in the UK?

- What are the current strengths and weaknesses of current arrangements, including for research?

- What measures could make the use of AI more transparent and explainable to the public?

- How should decisions involving AI be reviewed and scrutinised in both public and private sectors?

- Are current options for challenging the use of AI adequate and, if not, how can they be improved?

- How should the use of AI be regulated, and which body or bodies should provide regulatory oversight?

- To what extent is the legal framework for the use of AI, especially in making decisions, fit for purpose?

- Is more legislation or better guidance required?

- What lessons, if any, can the UK learn from other countries on AI governance?

This is the written evidence to the Committee from myself and Coran Darling, a Trainee Solicitor and member of the global tech and life sciences sectors at DLA Piper

Introduction

I, alongside Stephen Metcalfe MP, co-founded the All Party Parliamentary Group on Artificial Intelligence (“APPG”) in late 2016. The APPG is dedicated to informing parliamentarians of contextual developments and creating a community of interest around future policy regarding AI, its adoption, use, and regulation.

I was fortunate to then be asked to chair the House of Lords Special Enquiry Select Committee on AI with the remit: “to consider the economic, ethical, and social implications of advances in artificial intelligence”. As part of our work, the Select Committee produced its first report “AI in the UK: Ready Willing and Able?” in April 2018. The report looked closely at the current landscape of governmental policy towards the subject of AI and its ambitions for future development. This included, for example, those future plans contained in the Hall/Pesenti Review of October 2017, and those set out by former prime Minister Teresa May in her Davos World Economic Forum Speech, including her aim for the UK to “lead the world in deciding how AI can be deployed in a safe and ethical manner.”

Since then, as well as continuing to co-chair the APPG, I have maintained a close interest in the development of UK policy in AI, chaired a follow-up to the Select Committee’s report, “AI in the UK: No Room for Complacency”, acted as an adviser to the Council of Europe’s working party on AI (“CAHAI”) and helped establish the OECD Global Parliamentary Network on AI.

Lord Clement-Jones

25th November 2022

Background

The Hall Pesenti Review (“Review”) was an independent review commissioned in March 2017 tasked with reporting on the potential impact of AI on the UK economy. While it did not tackle the question of ethics or regulation of AI, the Review made several key recommendations designed to set a clear course for UK AI strategy including that:

- Data Trusts should be developed to provide proven and trusted frameworks to facilitate the sharing of data between organisations holding data and organisations looking to use data to develop AI;

- the Alan Turing Institute should become the national institute for AI and data science with the creation of an International Turing AI fellowship programme for AI in the UK; and

- the establishment of an UK AI Council to help coordinate and grow AI in the UK should occur.

The Government's subsequent “Industrial Strategy: building a Britain fit for the future” published in November 2017 (“Industrial Strategy”), identified putting AI “at the forefront of the UK’s AI and data revolution” as one of four 'Grand Challenges' identified as key to Britain's future. At the same time, the Industrial Strategy recognised that ethics would be key to the successful adoption of AI in the UK. This led to the establishment of the Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation in late 2018 with the remit to “make sure that data and AI deliver the best possible outcomes for society, in support of their ethical and innovative use”. In early 2018, the Industrial Strategy would go on to produce a £950m ‘AI Sector Deal’, which incorporated nearly all the recommendations of the Review and established a new Government Office for AI designed to coordinate their implementation.

Building on the work of the Review and the Industrial Strategy, the original Select Committee report enquiry concluded that the UK was in a strong position to be among the world leaders in the development of AI. Our recommendations were designed to support the Government and the UK in realising the potential of AI for our society and our economy and to protect from future potential threats and risks. It was concluded that the UK had a unique opportunity to forge a distinctive role for itself as a pioneer in ethical AI. We did, however, emphasise that if poorly handled, public confidence in AI could be undermined significantly.

In anticipation of the OECD’s subsequent digital AI principles, which were adopted in 2019, the Select Committee proposed five principles that could form the basis of a cross-sector AI code, and which could be adopted both nationally and internationally.

We did not at that point recommend a new regulatory body for AI-specific regulation, but instead noted that such a framework of principles could underpin regulation, should it prove to be necessary, in the future and that existing regulators would be best placed to regulate AI in their respective sectors. The Government in its response accepted the need to retain and develop public trust through an ethical approach both nationally and internationally.

In December 2020, the Select Committee’s follow up report “AI in the UK: No Room for Complacency” we examined the progress made by the Government to date since our earlier work. After interviews with government ministers, regulators, and other key players, the new report made several key recommendations. In particular, that:

- greater public understanding was essential for the wider adoption of AI and active steps should be taken by the Government to explain to the general public the use of their personal data by AI;

- the development of policy and mechanisms to safeguard the use of data, such as data trusts, needed to pick up pace, otherwise it risked being left behind by technological developments;

- the time had come for the Government to move from deciding what the ethics are to how to instil them in the development and deployment of AI systems. We called for the CDEI to establish and publish national standards for the ethical development and deployment of AI;

- users and policymakers needed to develop a better understanding of risk and how it can be assessed and mitigated, in terms of the context in which it is applied; and

- that coordination between the various bodies involved in the development of AI, including the various regulators, was essential. The Government therefore needed to better coordinate its AI policy and the use of data and technology by national and local government.

Despite the passage of time since the Industrial Strategy, the current governance of AI remains incomplete and unsatisfactory in several respects.

With respect to the use of data for training and inputs, such as for decision making and prediction, the UK General Data Protection Regulation (“GDPR”) and the Data Protection Act 2018 are important forms of governance. The Government’s “Data A New Direction” consultation however has led to a new Data Protection bill (“DP Bill”) which, while currently in development, proposes major changes to the GDPR post Brexit. These include significant amendments, such as no longer requiring firms to have a designated Data Protection Officer. The proposed DP Bill also waters down several provisions relating to data impact assessments. This holds the potential to create a divergence from the established data protection position in the UK and is likely to impact on the important EU Adequacy Decision in June 2021, leading to uncertainty for those wishing to use data for training and processing. The Government’s apparent intention to amend Article 22 of the GDPR giving the citizen the right not to be subjected to automated decision making also creates further uncertainty and runs the risk of a lower level of governance over decision made by AI systems.

A further area currently without a satisfactory approach is that of data and the issue of bias in decision making as a result of inherent bias caused by the improper use of data sets during the process of training algorithms. While it is likely that the Government’s own gap analysis will show that equalities legislation covers bias in acquired data which leads to discriminatory decisions made by AI, further consideration is needed on whether specific legal obligations in relation to the use of AI should be implemented in this context to actively mitigate its risk, rather than state that a discriminatory outcome is prohibited.

It is also the case that in many other areas of data and AI, there is no proper current governance in terms of binding legal duties that ensure that key internationally accepted ethical principles, such as those set out in the OECD AI Principles, are observed. These include:

- Inclusive growth, sustainable development and well-being;

- Human-centred values and fairness;

- Transparency and explainability;

- Robustness, security and safety; and

Despite the overall acceptance that the UK would need to consider developing policy or regulations in order to remain ahead of the curve, the UK’s National AI Strategy, published in September 2021, contained no discussion of ethics or regulation. Instead, an AI Governance whitepaper was promised to be published at some point in 2022.

Subsequent publication of an AI policy paper and AI Action Plan in July 2022 did however indicate that the Government was committed to developing “a pro-innovation national position on governing and regulating AI.” It is expected that this will be used to develop the AI Governance White paper.

Their approach is as follows:

“Establishing clear, innovation-friendly and flexible approaches to regulating AI will be core to achieving our ambition to unleash growth and innovation while safeguarding our fundamental values and keeping people safe and secure […] drive business confidence, promote investment, boost public trust and ultimately drive productivity across the economy.”

To facilitate its ‘pro-innovation’ approach, the Government has proposed several early cross-sectoral and overarching principles which build on the OECD AI Principles. These principles will, it seems, be interpreted and implemented by regulators within the context of the environment they oversee and will therefore be flexible to interpretation.

In terms of classification of AI within this ‘pro-innovation’ approach, rather than working to a clear definition of AI and determining what falls within scope, as chosen by the EU with their proposed AI Act, the UK has elected to follow an approach that instead sets out the core principles of AI which allows regulators to develop their own sector-specific definitions to meet the evolving nature of AI as technology advances.

In my view however, without a broad definition and some overarching duty to carry out a risk and impact assessment and subsequent regular audit to assess whether an AI system is conforming to Al principles, the governance of AI systems will be deficient, on the grounds alone that not every sector is regulated as is likely to be required. For example, except for certain specific products such as driverless cars there is no accountability or liability regime established for liability for the operation of AI systems at present.

This is the case for the public sector, as well as those in the private sector. While The Government has recognised the need for guidance for public sector organisations in the procurement and use of AI, it remains that there is no central and local government compliance mechanism to put this into practice. There are therefore insufficient measures of transparency, such as in the form of a public register of use of automated decision making, that require oversight and assessment of the decisions being carried out by AI in the context of public organisations. Furthermore, despite the efforts of parliamentarians, and organisations such as the Ada Lovelace Institute, there is no material recognition by the Government that explicit legislation, and/or regulation for intrusive AI technology such as live facial recognition, is needed to prevent the arrival of the surveillance state.

In light of the recognition by the National AI Strategy of the need to gain public trust, and for the wider use of trustworthy AI, the Government’s current proposals for a context specific approach are inadequate. In the face of this need to retain public trust, it must be clear, above all however, that regulation is not necessarily the enemy of innovation. In fact, it can in be the stimulus and key to gaining and retaining public trust around digital technology and its adoption. An approach by the Government could and should take the form of an overarching regulatory regime designed to ensure public transparency in the use of AI technologies and the recourse available across sectors for non-ethical use.

As is currently proposed, an approach which adopts divergent regulatory requirements across sectors would run the risk of creating barriers for developers and adopters through the requirement of having to navigate the regulatory obligations of multiple sectors. Where a cross-compatible AI system is concerned, for example in finance and telecoms, an organisation would have to potentially understand and comply with different regimes administered by the FCA, Prudential Regulation Authority, and Ofcom at the same time.

So, for these reasons, a much more horizontal cross sectoral approach than the Government is proposing is needed for the development and adoption of AI systems. This should set out clear common duties to assess risk and impact and adhere to common standards. Depending on the extent of the risk and impact assessed further legal duties would arise.

The question (What lessons, if any, can the UK learn from other countries on AI governance?) in my view should extend wider and ask not just about the lessons but the degree of harmonisation needed to ensure the most beneficial context for UK AI development, adoption, and assurance of ethical AI standards.

In its recent AI policy paper, a surprising admission is made by the Government that a context-driven approach may lead to less uniformity between regulators and may cause confusion and apprehension for stakeholders who will potentially need to consider multiple regimes, as well as the measures required to be taken to deal with extra-territorial obligations, such as those of the proposed EU AI Act.

International harmonisation is, in my view, essential if we wish to see developers and suppliers able to commercialise their products on a global basis assured that they are adhering to common standards of regulation without lengthy verification on entry of each individual jurisdiction in which they interact.

This could come in the form of a national version of the EU’s approach, where we have regulation that harmonises the landscape across sectors and industries, or in the form of international agreement on the standards of risk and impact assessment to be adopted. Work on common standards (i.e. the tools which would be deployed if regulation were out in place) is bearing fruit and may also assist organsiations in ensuring they are in conformity without navigating every subsector or jurisdiction with which they interact.

Most recently, we have seen the launch of the interactive AI Standards Hub by the Alan Turing institute with the support of the British Standards Institution and National Physical Laboratory which will provide users across industry, academia, and regulators with practical tools and educational materials to effectively use and shape AI technical standard. This in turn could lead to agreement on ISO standards with the EU and the US where NIST is actively engaged in developing similar protocols.

Having a harmonised approach would help provide the certainty businesses would need to develop and invest in the UK more readily.

When it comes to dealing with our nearest trading partner, it may be favourable to go one step further. When the White Paper does emerge, I believe that it is important that there is recognition that a considerable degree of convergence between us and EU is required practically, and that a risk-based form of horizontal, rather than purely sectoral, regulation is needed.

The Government is engaged in a great deal of activity. The question, therefore, is whether it is fast or focused enough and whether its objectives (such as achieving trustworthy AI and harmonised international standards) are going to be achieved through the actions being taken so far. As it stands currently, this does not look to be the case.

Lord Clement-Jones,

Coran Darling

Lord C-J at OECD : Mixed evidence on UK AI Governance

I recently attended a meeting of the OECD Global Parliamentary Network Group on Artificial Intelligence and spoke on UK developments during a session on Innovating in AI Legislation

It seems a long time since we all got together in person-what a pleasure! And such a pleasure to follow Eva. I am a huge admirer of what the EU have done in the AI space. I think we are all now beginning to be aware of the importance of digital media and the importance of AI and algorithms in our lives both positive and negative.Inevitably what I say is mainly focused on what we are doing in the UK but I hope it will have relevance in other jurisdictions.

The good news is that despite ( just a few!) changes in government or the pandemic UK government action on AI governance has been moving forward.

The UK’s National AI strategy - A ten-year plan for UK investment in and support of AI-was published in September 2021. It promised an AI Governance White Paper this year. In an AI policy paper and Action Plan published this July the Government then set out its emerging proposals for regulating AI in a policy consultation paper in which it committed to develop “a pro-innovation national position on governing and regulating AI.” This will be used to develop the White paper which may yet emerge this year.

Their approach would be “Establishing clear, innovation-friendly and flexible approaches to regulating AI will be core to achieving our ambition to unleash growth and innovation while safeguarding our fundamental values and keeping people safe and secure. …….drive business confidence,promote investment, boost public trust and ultimately drive productivity across the economy.” Fine words but we now have some more detailed clues as to the future of regulation of AI in the UK.

As regards categorising AI rather than working to a clear definition of AI determining what falls within scope, which is the approach taken by the EU Regulation, the UK has elected to follow an approach that instead sets out the core principles of AI which allows regulators to develop their own sector-specific definitions to meet the evolving nature of AI as technology advances.

In a surprising admission the policy paper does acknowledge that a context-driven approach may lead to less uniformity between regulators and may cause confusion and apprehension for stakeholders who will potentially need to consider the regime of multiple regulators as well as the measures required to be taken to deal with extra-territorial regimes, such as the EU Regulation.

To facilitate its ‘pro-innovation’ approach, the UK Government however has proposed several early cross-sectoral and overarching principles which build on the OECD ‘Principles on Artificial Intelligence’ . These principles will be interpreted and implemented by regulators within the context of the environment they oversee and would therefore be flexible to interpretation. This call for views and evidence closed on 26 September so we shall see what emerges in the White paper probably not this year!!

As a result of this context-driven approach the regulators in different sectors are going to take centre stage. So it is timely that 4 of our key regulators the ICO OFCOM CMA FCA have got together under a new Digital Regulators Cooperation Forum to pool expertise in this field. This includes sandboxing and input from a variety of expert institutes such as the Alan Turing Institute on areas such as risk assessment, AI, audit, digital design frameworks and standards digital advertising and horizon scanning

The policy paper in turn has led to the launch this October of the interactive hub platform AI Standards Hub led by the Alan Turing institute with the support of the British Standards Institution and National Physical Laboratory which will provide users across industry, academia and regulators with practical tools and educational materials to effectively use and shape AI technical standards.

All this represents action but while the National AI strategy paper of last September does talk about public trust and the need for trustworthy AI,my view is that it needs to be reflected in how we regulate. In the face of the need to retain public trust we need to be clear, above all, that regulation is not necessarily the enemy of innovation, it can in fact be the stimulus and be the key to gaining and retaining public trust around digital technology and its adoption so we can realise the benefits and minimise the risks.

International harmonization is in my view essential if we are to see developers able to commercialize their products on a global basis assured that they are adhering to common standards of regulation. One of my regrets is that the UK government unlike our technical experts doesn’t devote enough attention to positive collaboration in a number of international AI fora such as the Council of Europe, UNESCO And the OECD

But the UK IS playing an active part in GPAI serviced by the OECD which is beginning to deliver some interesting output particularly in respect of the workplace. I hope too that when the White Paper does emerge that there is recognition that we need a considerable degree of convergence between ourselves the EU, members of the COE and the OECD in particular, for the benefit of our developers and cross border business that recognizes that a risk based form of horizontal rather than purely sectoral regulation is required.

Above all this means agreeing on standards for risk and impact assessments alongside tools for audit and continuous monitoring for higher risk applications..That way I believe we can draw the US into the fold as well.

Other aspects of policy where I do NOT believe we are heading in the right direction however are

Data :The government’s “Data A New Direction” consultation has led to a new Data Protection bill. Despite little appetite in the business or the research communities they are proposing major changes to the GDPR post Brexit including not requiring firms to have a DPO or DPIA. All this is likely to impact on the precious EU Adequacy Decision which was made in June 21 and is meant to last for 4 years.

IP: Our Intellectual Property Office too is currently grappling with issues relating to IP created by AI . Artificial Intelligence and Intellectual Property: copyright and patents consultation closed January 2022 and now has recommended changes to text and data mining exemption which has been very widely criticised by the creative industries, publishers etc.

In addition although the UK Government has recognized the need for any amount of guidance for public sector organizations there is no central and local government compliance mechanism and little transparency in the form of a public register of use of automated decision making.

We also, despite the efforts of Parliamentarians and organisations such as the Ada Lovelace Institute, have no recognition at all that regulation for intrusive AI technology such as live facial recognition is needed.

We are still having a major debate on the deployment over live facial recognition technology -the use of biometrics and AI - in policing, schools and in criminal justice recently. Many of us have real concern that we are approaching the surveillance state.

In addition there is little appetite in government to ensure that our employment laws protect the increasing number of workers in the gig economy whose lives can be ruled by algorithm without redress.

So our government is engaged in a great deal of activity, the question as ever is whether it is fast or focused enough and whether the objectives such as achieving trustworthy AI and harmonized international standards are going to be achieved through the actions being taken so far. As you’ve heard today, I believe the evidence of success is still mixed! I still have quite a political shopping list!

How to Make the UK the Best Place in the World for Artificial Intelligence.

I recently gave a talk at a meeting of members of The Entrepreneurs Network. This is slightly expanded version.

It's pleasure to be in Entrepreneurial company tonight

The Truss/Kwarteng paradise of Britannia Unchained to unleash growth, growth growth has been showed up for what it it was. It didn’t outlast a lettuce. I hope that with Rishi Sunak as PM we are at the end of the magical thinking era.

I am always an optimist but I look forward to hearing whether you agree with Guy Hands who thinks we’re going to be the sick man of Europe.

So I’m not going to talk at you too long and I’m certainly not going to get into detailed expenditure or taxation proposals! That would be bound to get me into trouble.

And the first thing to remember is that policy is all very well but its results that matter and government can be the graveyard for good ideas, innovation and enterprise. You only have to read Kate Bingham’s recent book Long Shot to understand how bureaucratic process can so easily be a killer of good intentions and effective outcomes.

The second is that we are in my view fighting a combination of factors including the effects of COVID Brexit, Austerity, and political instability to put it mildly. Mathew Syed in his Sunday Times column headlined that an “Irrational faith in the providence of Brexit has trapped adherents in cognitive dissonance and denial” . We need a frank appraisal of the impact of Brexit and fix the consequences where we can.

So our economic circumstances really do require prioritisation and clear thinking.

What I would like to do is throw out a few thoughts for discussion on where the focus of government policy should be in order to grow our tech sector in general and AI development and adoption in particular.

The challenges include.

- how can we convert academic success into entrepreneurship?

- How can we increase the speed of business adoption of AI tech in the UK?

- How can we best guard against future harms that AI could bring?

I am saying all this of course in the light of the Government’s grand 10 year plan “Make Britain a global AI superpower” published a year ago.

Let’s briefly consider a number of key priority areas :

- The need for quality data

- Good regulation and standards which gain public trust

- Jobs and Skills

- International cooperation especially in R&D eg Horizon

- Investment incentives

- Infrastructure

TechUk reported earlier this year at London Tech Week that UK start-up investment saw the biggest annual opening on record in 2022, with $11.3B raised by UKstart-ups in Q1, compared to $7.9b in Q1 2021.The UK is home to 122 unicorns, behind only the USand China for the creation of billion dollar tech companies, and first in Europe..

This is undoubtedly positive, especially considering the wider economic challenges the UK and the world face. However, with the UK economy forecasted to face a recession and an economic slowdown forecasted for 2023-2026, we cannot be complacent,

Moreover as the Entrepreneurs Network point out in your recent paper making Britain the best place for AI Innovation, while the UK is a global leader in research, development and talent, the Tortoise Index ranks Government strategy - defined as financial and procedural investment into AI - only 13th internationally, which puts it behind Belgium.

First of all if we are to have an AI growth Strategy there is need for a quality data

We need independent measures of platform business, their economic activity, growth rates, national and regional figures that can reveal hotspots of growth as well as cold spots for future investment and development.It seems that organisations such as the ONS don’t gather relevant data. It is difficult to develop a growth strategy for AI when the baseline from which to compare the growth isn't available.

We also need data that cover different dimensions of growth –there need to be quality measures – quality of jobs, income, service, work/life balance etc.

Good regulation and standards

Then we have the importance of certainty for business of clear regulation.progress on AI governance and regulation is important as well to restore and retain Public Trust..

Regulation is not necessarily the enemy of innovation, it can in fact be the stimulus and be the key to gaining and retaining public trust around AI and its adoption

One of the main areas of focus of our original AI Select Committee was the need to develop an appropriate ethical framework for the development and application of AI and we were early advocates for international agreement on the principles to be adopted. It has become clear that voluntary ethical guidelines however much they are widely shared, are not enough to guarantee ethical AI and gain trust.

Some of the institutions envisaged as the core of AI development really are working well. The Turing for example is coordinating effectively such as through the new AI Standards Hub But CDEI has lost its way and not been given enough independence and the Office for AI has lost impetus. The Digital Catapult has considerable expertise and great potential but is underresourced.

A key development in the last two years has been the work done at international level in the Council of Europe, OECD, UNESCO and EU towards putting these principles into practice . The only international forum where the government seem to want to make a real contribution however is the global partnership on AI GPAI

If at minimum we could agree international standards for AI Risk Assessment and Audit that would represent realm progress and give our developers real certainty.

The UK’s National AI strategy accepts the fact that we need to prepare for AGI

On the other hand despite little appetite in the business or the research communities they have now introduced a new a really unhelpful Bill on major changes to the GDPR post Brexit and as a result we may have a less independent ICO which will put at risk the precious Data Adequacy ruling by the EU.

And above all despite their commitment to trustworthy AI, we still await the Government’s proposals on AI Governance in the forthcoming White Paper but there is a strong prediction that it will be mainly sectoral;/contextual and not in line with our EU partners or even extraordinarily the US.

At the very least we also need to be mindful that the extraterritoriality of the EU AI Act means a level of regulatory conformity will be required for the benefit of our developers and cross border business

Jobs and Skills

Then of course we have the potential impact of AI on jobs and employment . A report by Microsoft quoted by TEN found that the UK is facing an AI skills shortage: only 17% of UK employees are being re-skilled for AI

We need to ensure that people have the opportunity to reskill and retrain to be able to adapt to the evolving labour market caused by AI. Every child should leave school with a basic sense of how AI works.

But the pace, scale and ambition of government action does not match the challenge facing many people working in the UK. The Skills and post 16 Education Act with its introduction of a Lifelong Loan Entitlement is a step in the right direction.I welcome the renewed emphasis on Further Education and the new institutes of Technology.. but this isn’t ambitious enough.

The government refer to AI apprenticeships but Apprentice Levy reform is long overdue. The work of Local Digital Skills Partnerships and Digital Boot camps is welcome but they are greatly under-resourced and only a patchwork. Careers advice and Adult education need a total revamp

We also need to attract foreign talent. Immigration has a positive impact on innovation.The new Global Talent visa seeks to attract leaders or potential leaders in various fields including digital technology. This and changes the changes to the Innovator visa are welcome.

Broader digital literacy is crucial. We need to learn how to live and work alongside AI and a specific training scheme should be designed to support people to work alongside AI and automation, and to be able to maximise its potential

Given the current and imminently greater disruption in the job market we need to modernise employment rights to make them fit for the age of the AI driven ‘gig economy’, in particular by establishing a new ‘dependent contractor’ employment status in between employment and self-employment, with entitlements to basic rights such as minimum earnings levels, sick pay and holiday entitlement.

Alongside this we shared the priority of the AI Council Roadmap for more diversity and inclusion in the AI workforce and we still need to see more progress in this area.

R & D support including International cooperation eg Horizon

Any industrial policy for AI needs to discuss the R & D and innovation context in which it is designed to sit.

The UK has/had a long-term target for UK R&D to reach 2.4% of GDP by 2027. In 2020 we had the very well-intentioned R & D Roadmap. Since then we have had the UK Innovation Strategy with its Vision 2035, the AI Strategy, the Lifesciences Vision, the Fintech Strategic Review, all it seems informed by the Integrated Review’s determination that we will have secured our status as a science and tech superpower by 2030.

So there is no shortage of roadmaps, reviews and strategies which lay out government policy in this landscape!

Lord Hague wrote a wise piece in the Times a little time ago. he said

“But the officials working on so many new strategies should be running down the corridors by now and told to come back only when they have some detailed plans that go far beyond expressing our ambitions”

When we wrote our AI reports in 2018 and 2020 it was clear to us that the UK remained attractive to international research talent. I am still very enthusiastic about the future of UK research & development, innovation and their commercial translation in the UK and want them to thrive for all our benefit

University R& D remains important.There are strong concerns about the availability of research visas available for entrance to universities research programmes and the failure to agree and the lack of access to EU Horizon research Council funding could have a huge impact. Plan B by the sound of it won’t give us anything like the same benefits. A number of Russell group universities such as imperial UCL and my own Queen Mary are now with finance partners building spin out funds.

Additional funding could be provided to leading research universities to fund postgraduate scholarships in AI-related fields. .We should be seeking to make universities regional powerhouses tied in with the economic future of our city regions through university enterprise zones

We do nevertheless rank highly in the world of early-stage research and some late stage not least in AI, but it is in commercialisation- translational research and industrial R&D-where we continue to fall down.

The UK is a top nation in the global impact of its R&D, but not so effective at innovation, where it ranks 11th in the world in terms of knowledge diffusion and 27th for knowledge absorption, according to an October 2021 report by BEIS.

As Lord Willets is quoted as saying in a recent excellent HEPI paper (see how i quote tory peers!) “Catching the wave: harnessing regional research and development to level up ‘We all know the problem– we have great universities and win Nobel Prizes, but we don’t do so well at commercialisation’.

Our research sponsoring bodies could be more generous in their funding, with less micromanagement, less keen digging up projects by the roots to see if they are growing. The creation of ARIA was an admission of the bureaucratic nature the current UKRI research funding system

I welcome moves to extend R&D tax credits to investment in cloud computing infrastructure and data cost, but We need to bring in capital expenditure costs, such as those on plant and machinery for facilities engaging in R&D within scope as Tech UK have called for.I think we should now consider for AI investment something akin to the dedicated film tax credit for AI investment which has been so successful to date.

There needs to be more support for Catapults which have crucial roles as technology and innovation centre as the House of Lords Science and Technology Committee Report this year recommended

We could also emulate America’s seed fund- the SBIR and STTR programs which are at much great scale than our albeit successful UK Innovation and Science Seed Fund (UKI2S). And we need to expand the role of our low profile British Business bank

Infrastructure

There has been so much government bravado in this area but is clear that the much trumpeted £5 billion announced last year for Project Gigabit bringing gigabit coverage to the hardest to reach areas has not even been fully allocated and barely a penny has been spent.

But the Government is still not achieving its objectives.

The latest Ofcom figures show it seems that 90% of houses are covered by superfast broadband but the urban rural gap is still wide.

While some parts of the country are benefiting from high internet speeds, others have been left behind, The UK has nearly 5mn houses with more than three choices of ultrafast fibre optic broadband, while 10mn homes do not have a single option. According to the latest government data, in January 2022, 70 per cent of urban premises across the UK had access to gigabit-capable broadband, compared with 30 per cent of rural ones.

In fact urban areas now risk being overbuilt with fibre. In many towns and cities, at least three companies are digging to lay broadband fibre cables all targeting the same households, with some areas predicted to have six or seven such lines by the end of the decade.

So are we now into a wild west for the laying of fibre optic cable Is this going to be like the Energy market with great numbers of companies going bust.

So sadly even our infrastructure rollout is not very coherent!

.

Freedom of Expression Compatible with Child Protection says Lord C-J

The House of Lords recently debated the report of the Communivccations and digitl Select Committee Repotry entitled Free For All? Freedom of Expression in the Digital Age.

This is an edited version of what I said in the debate.

I congratulate the Select Committee on yet another excellent report relating to digital issues It really has stimulated some profound and thoughtful speeches from all around the House. This is an overdue debate.

As someone who sat on the Joint Committee on the draft Online Safety Bill, I very much see the committee’s recommendations in the frame of the discussions we had in our Joint Committee. It is no coincidence that many of the Select Committee’s recommendations are so closely aligned with those of the Joint Committee, because the Joint Committee took a great deal of inspiration from this very report—I shall mention some of that as we go along.

By way of preface, as both a liberal and a Liberal, I still take inspiration from JS Mill and his harm principle, set out in On Liberty in 1859. I believe that it is still valid and that it is a concept which helps us to understand and qualify freedom of speech and expression. Of course, we see Article 10 of the ECHR enshrining and giving the legal underpinning for freedom of expression, which is not unqualified, as I hope we all understand.

There are many common recommendations in both reports which relate, in the main, to the Online Safety Bill—we can talk about competition in a moment. One absolutely key point made during the debate was the need for much greater clarity on age assurance and age verification. It is the friend, not the enemy, of free speech.

The reports described the need for co-operation between regulators in order to protect users. On safety by design, both reports acknowledged that the online safety regime is not essentially about content moderation; the key is for platforms to consider the impact of platform design and their business models. Both reports emphasised the importance of platform transparency. Law enforcement was very heavily underlined as well. Both reports stressed the need for an independent complaints appeals system. Of course, we heard from all around the House today the importance of media literacy, digital literacy and digital resilience. Digital citizenship is a useful concept which encapsulates a great deal of what has been discussed today.

The bottom line of both committees was that the Secretary of State’s powers in the Bill are too broad, with too much intrusion by the Executive and Parliament into the work of the independent regulator and, of course, as I shall discuss in a minute, the “legal but harmful” aspects of the Bill. The Secretary of State’s powers to direct Ofcom on the detail of its work should be removed for all reasons except national security.

A crucial aspect addressed by both committees related to providing an alternative to the Secretary of State for future-proofing the legislation. The digital landscape is changing at a rapid pace—even in 2025 it may look entirely different. The recommendation—initially by the Communications and Digital Committee—for a Joint Committee to scrutinise the work of the digital regulators and statutory instruments on digital regulation, and generally to look at the digital landscape, were enthusiastically taken up by the Joint Committee.

The committee had a wider remit in many respects in terms of media plurality. I was interested to hear around the House support for this and a desire to see the DMU in place as soon as possible and for it to be given those ex-ante powers.

Crucially, both committees raised fundamental issues about the regulation of legal but harmful content, which has taken up some of the debate today, and the potential impact on freedom of expression. However, both committees agreed that the criminal law should be the starting point for regulation of potentially harmful online activity. Both agreed that sufficiently harmful content should be criminalised along the lines, for instance, suggested by the Law Commission for communication and hate crimes, especially given that there is now a requirement of intent to harm.

Under the new Bill, category 1 services have to consider harm to adults when applying the regime. Clause 54, which is essentially the successor to Clause 11 of the draft Bill, defines content that is harmful to adults as that

“of a kind which presents a material risk of significant harm to an appreciable number of adults in the United Kingdom.”

Crucially, Clause 54 leaves it to the Secretary of State to set in regulations what is actually considered priority content that is harmful to adults.

The Communications and Digital Committee thought that legal but harmful content should be addressed through regulation of platform design, digital citizenship and education. However, many organisations argue especially in the light of the Molly Russell inquest and the need to protect vulnerable adults, that we should retain Clause 54 but that the description of harms covered should be set out in the Bill.

Our Joint Committee said, and I still believe that this is the way forward:

“We recommend that it is replaced by a statutory requirement on providers to have in place proportionate systems and processes to identify and mitigate reasonably foreseeable risks of harm arising from regulated activities defined under the Bill”, but that

“These definitions should reference specific areas of law that are recognised in the offline world, or are specifically recognised as legitimate grounds for interference in freedom of expression.”

We set out a list which is a great deal more detailed than that provided on 7 July by the Secretary of State. I believe that this could form the basis of a new clause. As my noble friend Lord Allan said, this would mean that content moderation would not be at the sole discretion of the platforms. The noble Lord, Lord Vaizey, stressed that we need regulation.

We also diverged from the committee over the definition of journalistic content and over the recognised news publisher exemption, and so on, which I do not have time to go into but which will be relevant when the Bill comes to the House. But we are absolutely agreed that regulation of social media must respect the rights to privacy and freedom of expression of people who use it legally and responsibly. That does not mean a laissez-faire approach. Bullying and abuse prevent people expressing themselves freely and must be stamped out. But the Government’s proposals are still far too broad and vague about legal content that may be harmful to adults. We must get it right. I hope the Government will change their approach: we do not quite know. I have not trawled through every amendment that they are proposing in the Commons, but I very much hope that they will adopt this approach, which will get many more people behind the legal but harmful aspects.

That said, it is crucial that the Bill comes forward to this House. Lord Gilbert, pointed to the Molly Russell inquest and the evidence of Ian Russell, which was very moving about the damage being wrought by the operation of algorithms on social media pushing self-harm and suicide content. I echo what the noble Lord said: that the internet experience should be positive and enriching. I very much hope the Minister will come up with a timetable today for the introduction of the Online Safety Bill.

At last... compensation for Hep C blood victims

Finally after 5 decades Haemophiliac victims of the contaminted Hepatitisis C blood scandal are due to receive compensation as a result of the recommendation of the Langstaff Enquiry ...although not their familes.

Something that successive governments of all parties have failed to do.

It reminds me that TWENTY YEARS AGO when I was the Lib Dem Health Spokesperson in the Lords we were arging for an enquiry and compensation from the Blair Government. Only now 2 decades later has it become a reality.

This is what I said at the time in a debate in April 2001 initiated by the late Lord Alf Morris, that great campaigner for the disabled, asking the government : "What further help they are considering for people who were infected with hepatitis C by contaminated National Health Service blood products and the dependants of those who have since died in consequence of their infection."

My Lords, I believe that the House should heartily thank the noble Lord, Lord Morris, for raising this issue yet again. It is unfortunate that I should have to congratulate the noble Lord on his dogged persistence in raising this issue time and time again. I can remember at least two previous debates this time last year and another in 1998. I remember innumerable Starred Questions on the subject, and yet the noble Lord must reiterate the same issues and points time and time again in debate. It is extremely disappointing that tonight we hold yet another debate to point out the problems faced by the haemophilia community as a result of the infected blood products with which the noble Lord has so cogently dealt tonight.

Many of us are only too well acquainted with the consequences of infected blood products which have affected over 4,000 people with haemophilia. We know that as a consequence up to 80 per cent of those infected will develop chronic liver disease; 25 per cent risk developing cirrhosis of the liver; and that between one and five per cent risk developing liver cancer. Those are appalling consequences.