Broadband and 5G rollout strategy needs review

During the passage of the Product and Security Bill it has become clear that the Government's rollout strategy keeps being changed and is unlikely to achieve its objectives, especially in rural areas. This is what I said when supporting a review.

We all seem to be trapped in a time loop on telecoms, with continual consultations and changes to the ECC and continual retreat by the Government on their 1 gigabit per second broadband rollout pledge. In the Explanatory Notes, we were at 85% by 2025; this now seems to have shifted to 2026. There has been much government bravado in this area, but it is clear that the much-trumpeted £5 billion announced last year for project gigabit, to bring gigabit coverage to the hardest-to-reach areas, has not yet been fully allocated and that barely a penny has been spent.

Then, we have all the access and evaluation amendments to the Electronic Communications Code and the Digital Economy Act 2017. Changes to the ECC were meant to do the trick; then, the Electronic Communications and Wireless Telegraphy (Amendment) (European Electronic Communications Code and EU Exit) Regulations were heralded as enabling a stronger emphasis on incentivising investment in very high capacity networks, promoting the efficient use of spectrum, ensuring effective consumer protection and engagement and supporting the Government’s digital ambitions and plans to deliver nationwide gigabit-capable connectivity.

Then we had the Future Telecoms Infrastructure Review. We had the Telecommunications Infrastructure (Leasehold Property) Act—engraved on all our hearts, I am sure. We argued about the definition of tenants, rights of requiring installation and rights of entry, and had some success. Sadly, we were not able to insert a clause that would have required a review of the Government’s progress on rollout. Now we know why. Even while that Bill was going through in 2021, we had Access to Land: Consultation on Changes to the Electronic Communications Code. We knew then, from the representations made, that the operators were calling for other changes not included in the Telecommunications Infrastructure (Leasehold Property) Act or the consultation. From the schedule the Minister has sent us, we know that he has been an extremely busy bee with yet further discussions and consultations.

I will quote from a couple of recent Financial Times pieces demonstrating that, with all these changes, the Government are still not achieving their objectives. The first is headed: “Broadband market inequalities test Westminster’s hopes of levelling up: Disparity in access to fast internet sets back rural and poorer areas, data analysis shows”. It starts:

“The UK has nearly 5mn houses with more than three choices of ultrafast fibre-optic broadband, while 10mn homes do not have a single option, according to analysis that points to the inequality in internet infrastructure across Britain.

While some parts of the country are benefiting from high internet speeds, others have been left behind, according to research conducted by data group Point Topic with the Financial Times, leading to disparities in people’s ability to work, communicate and play.”

A more recent FT piece from the same correspondent, Anna Gross, is headed: “UK ‘altnets’ risk digging themselves into a hole: Overbuilding poses threat to business model of fibre broadband groups challenging the big incumbents”. It starts:

“Underneath the UK’s streets, a billion-pound race is taking place. In many towns and cities, at least three companies are digging to lay broadband fibre cables all targeting the same households, with some areas predicted to have six or seven such lines by the end of the decade.

But only some of them will cross the finishing line … When the dust settles, will there be just two network operators—with Openreach and Virgin Media O2 dominating the landscape—or is there space for a sparky challenger with significant market share stolen from the incumbents?”

Are we now in a wild west for the laying of fibre-optic cable? Will this be like the energy market, with great numbers of companies going bust?

By contrast, INCA, the Independent Networks Cooperative Association, reports in its latest update:

“The ‘AltNets’ have more than doubled their footprint year on year since 2019”—

I think my noble friend Lord Fox quoted these figures—

“now reaching 5.5m premises and expected to reach 11.5m premises by the end of this year. Investment remains buoyant with an additional £5.7bn committed during 2021 bringing total estimated investment in the independent sector to £17.7bn for the period to 2025.”

We have two very different stories there. What contingencies have the Government made? Who will pick up the tab if the former scenario is correct—the poor old consumer? In any event, will rural communities get any service in the end?

What of rural broadband rollout? It appears that DCMS is currently assessing policy options on the means of best addressing the shortfall. I was interested to hear the very pointed question that the noble Baroness, Lady Merron, asked about what working groups were examining some of these issues, following a call for evidence on improving broadband for very hard-to-reach areas. What is the department actually doing? Can we expect more changes to the ECC?

The policy justification for the 2017 reforms was that rent savings by operators would be reinvested in networks, with the then Minister saying that the Government would hold operators’ feet to the fire to ensure that they delivered, noting that to

“have real impact, savings must be invested in expanding network infrastructure”.—[Official Report, 31/1/17; col. 1157.]

and saying that the revised code secured real investment. This was supported by confirmation, in the impact assessment accompanying the reforms to the ECC in 2017, that the Government would review the impact of the policy by June 2022. But this has not been met, despite the Government’s future infrastructure review confirming that they were already considering undertaking a formal review of the code reforms to assess their impact in 2019. The Government’s decision to introduce new legislation proves that the 2017 reforms have not actually achieved their aims.

Instead of leading to faster and easier deployment, as we have heard today, changes to the rights given to operators under the code have stopped the market working as it should and led to delays in digital rollout, as well as eroding private property rights. This has resulted in small businesses facing demands for rent reductions of over 90%; a spike in mobile network operators bringing protracted litigation; failure by mobile operators to reinvest their savings in mobile infrastructure; and delayed 5G access for up to 9 million people, at a cost of over £6 billion to the UK economy. The Government’s legislation and their subsidies now show they know the reforms have failed. That is why they are passing new legislation to revise the code, as well as announcing £500 million in new subsidies for operators through the shared rural network.

In Committee in the other place, the Minister, Julia Lopez, claimed:

“If a review takes place, stakeholders will likely delay entering into agreements to enable the deployment of infrastructure. Only when the review has concluded and it is clear whether further changes are to be made to the code will parties be prepared to make investment or financial commitments”.—[Official Report, Commons, Product Security and Telecommunications Infrastructure Bill Committee, 22/3/22; col. 122.]

In addition to there being no evidence for this claim, this extraordinary line of reasoning would allow the Government to escape scrutiny and commitments in a wide variety of policy areas, were it applied more broadly. To maintain public faith in policy-making, it is vital that there is an accessible evidence base on which decisions are made. The Government’s decisions in this Bill do not meet the standard.

Moreover, I know that Ministers are sceptical about the Centre for Economics and Business Research’s report. The noble Lord, Lord Parkinson, has said that it oversimplifies the issue, but I do not believe that the Government have properly addressed some of the issues raised in it. The CEBR is an extremely reputable organisation and although the research was commissioned by Protect and Connect, the Government need to engage in that respect.

Our amendment would insert a new clause obliging the Government to commission an independent review of the impact of the legislation and prior reforms within 18 months. The review would assess the legislation’s impact on the rate of additional investment in mobile networks and infrastructure deployment, the costs borne by property owners and the wider benefit or costs of the legislation. It would also oblige the Government to publish a response to the review within 12 weeks of its publication and lay that before Parliament, to ensure parliamentary accountability for the Government’s action and to allow debate.

Another amendment would insert a new clause placing obligations on operators to report certain information to Ofcom each year. Operators would have to report on such information as their overall investment in mobile networks, the rent paid to site providers, the number of new mobile sites built within the UK, and upgrades and renewals.

It is the final group in Committee, so where in all this—as my noble friend Lord Fox and I have been asking each time we debate these issues—are the interests of the consumer, especially the rural consumer? How are they being promoted, especially now that market review is only once every five years? That is why we need these reviews in these amendments. We tried in the last Bill to make the Government justify their strategy. Now it is clear that changes to the ECC are not fit for purpose and we will try again to make the Government come clean on their strategy.

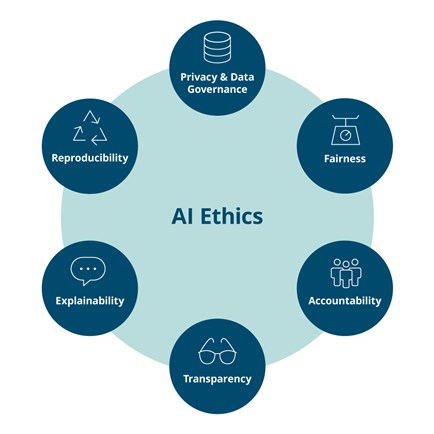

Government AI Procurement needs ethical and data compliance obligation

The Procurement Bill lacks any kinds of obligation on Government to ensure that AI systems procred comply with ethical and data protection principles despite numerous guidelines bering issed. This is what I said when proposing a new clause designed to ensure this.

In our report AI in the UK: Ready, Willing and Able?, our AI Lords Select Committee, which I chaired, expressed its strong belief in the value of procurement by the public sector of AI applications. However, as a recent research post put it:

“Public sector bodies in several countries are using algorithms, AI, and similar methods in their administrative functions that have sometimes led to bad outcomes that could have been avoided.”

The solution is:

“In most parliamentary democracies, a variety of laws and standards for public administration combine to set enough rules to guide their proper use in the public sector.”

The challenge is to work out what is lawful, safe and effective to use.

The Government clearly understand this, yet one of the baffling and disappointing aspects of the Bill is the lack of connection to the many government guidelines applying to the procurement and use of tech, such as artificial intelligence and the use and sharing of data by those contracting with government. It is unbelievable, but it is almost as if the Government wanted to be able to issue guidance on the ethical aspects of AI and data without at the same time being accountable if those guidelines are breached and without any duty to ensure compliance.

There is no shortage of guidance available. In June 2020, the UK Government published guidelines for artificial intelligence procurement, which were developed by the UK Government’s Office for Artificial Intelligence in collaboration with the World Economic Forum, the Government Digital Service, the Government Commercial Function and the Crown Commercial Service. The UK was trumpeted as the first Government to pilot these procurement guidelines. Their purpose is to provide central government departments and other public sector bodies with a set of guiding principles for purchasing AI technology. They also cover guidance on tackling challenges that may occur during the procurement process. In connection with this project, the Office for AI also co-created the AI procurement toolkit, which provides a guide for the public sector globally to rethink the procurement of AI.

As the Government said on launch,

“Public procurement can be an enabler for the adoption of AI and could be used to improve public service delivery. Government’s purchasing power can drive this innovation and spur growth in AI technologies development in the UK.

As AI is an emerging technology, it can be more difficult to establish the best route to market for your requirements, to engage effectively with innovative suppliers or to develop the right AI-specific criteria and terms and conditions that allow effective and ethical deployment of AI technologies.”

The guidelines set out a number of AI-specific considerations within the procurement process:

“Include your procurement within a strategy for AI adoption … Conduct a data assessment before starting your procurement process … Develop a plan for governance and information assurance … Avoid Black Box algorithms and vendor lock in”,

to name just a few. The considerations in the guidelines and the toolkit are extremely useful and reassuring, although not as comprehensive or risk-based as some of us would like, but where does any duty to adhere to the principles reflecting them appear in the Bill?

There are many other sets of guidance applicable to the deployment of data and AI in the public sector, including the Technology Code of Practice, the Data Ethics Framework, the guide to using artificial intelligence in the public sector, the data open standards and the algorithmic transparency standard. There is the Ethics, Transparency and Accountability Framework, and this year we have the Digital, Data and Technology Playbook, which is the government guidance on sourcing and contracting for digital, data and technology projects and programmes. There are others in the health and defence sectors. It seems that all these are meant to be informed by the OECD’s and the G20’s ethical principles, but where is the duty to adhere to them?

It is instructive to read the recent government response to Technology Rules?, the excellent report from the Justice and Home Affairs Committee, chaired by my noble friend Lady Hamwee. That response, despite some fine-sounding phrases about responsible, ethical, legitimate, necessary, proportionate and safe Al, displays a marked reluctance to be subject to specific regulation in this area. Procurement and contract guidelines are practical instruments to ensure that public sector authorities deploy AI-enabled systems that comply with fundamental rights and democratic values, but without any legal duty backing up the various guidelines, how will they add up to a row of beans beyond fine aspirations? It is quite clear that the missing link in the chain is the lack of a legal duty to adhere to these guidelines.

My amendment is formulated in general terms to allow for guidance to change from time to time, but the intention is clear: to make sure that the Government turn aspiration into action and to prompt them to adopt a legal duty and a compliance mechanism, whether centrally via the CDDO, or otherwise.

Debate on AI in the UK: No Room For Complacency report

Recently the House of Lords belatedly debated the follow Report to the the original House of Lords AI Committee Report AI Report No Room for Complacency . This is how I introduced it:

My Lords, the Liaison Committee report No Room for Complacency was published in December 2020, as a follow-up to our AI Select Committee report, AI in the UK: Ready, Willing and Able?, published in April 2018. Throughout both inquiries and right up until today, the pace of development here and abroad in AI technology, and the discussion of AI governance and regulation, has been extremely fast moving. Today, just as then, I know that I am attempting to hit a moving target. Just take, for instance, the announcement a couple of weeks ago about the new Gato—the multipurpose AI which can do 604 functions —or perhaps less optimistically, the Clearview fine. Both have relevance to what we have to say today.

First, however, I say a big thank you to the then Liaison Committee for the new procedure which allowed our follow-up report and to the current Lord Speaker, Lord McFall, in particular and those members of our original committee who took part. I give special thanks to the Liaison Committee team of Philippa Tudor, Michael Collon, Lucy Molloy and Heather Fuller, and to Luke Hussey and Hannah Murdoch from our original committee team who more than helped bring the band, and our messages, back together.

So what were the main conclusions of our follow-up report? What was the government response, and where are we now? I shall tackle this under five main headings. The first is trust and understanding. The adoption of AI has made huge strides since we started our first report, but the trust issue still looms large. Nearly all our witnesses in the follow-up inquiry said that engagement continued to be essential across business and society in particular to ensure that there is greater understanding of how data is used in AI and that government must lead the way. We said that the development of data trusts must speed up. They were the brainchild of the Hall-Pesenti report back in 2017 as a mechanism for giving assurance about the use and sharing of personal data, but we now needed to focus on developing the legal and ethical frameworks. The Government acknowledged that the AI Council’s roadmap took the same view and pointed to the ODI work and the national data strategy. However, there has been too little recent progress on data trusts. The ODI has done some good work, together with the Ada Lovelace Institute, but this needs taking forward as a matter of urgency, particularly guidance on the legal structures. If anything, the proposals in Data: A New Direction, presaging a new data reform Bill in the autumn, which propose watering down data protection, are a backward step.

More needs to be done generally on digital understanding. The digital literacy strategy needs to be much broader than digital media, and a strong digital competition framework has yet to be put in place. Public trust has not been helped by confusion and poor communication about the use of data during the pandemic, and initiatives such as the Government’s single identifier project, together with automated decision-making and live facial recognition, are a real cause for concern that we are approaching an all-seeing state.

My second heading is ethics and regulation. One of the main areas of focus of our committee throughout has been the need to develop an appropriate ethical framework for the development and application of AI, and we were early advocates for international agreement on the principles to be adopted. Back in 2018, the committee took the view that blanket regulation would be inappropriate, and we recommended an approach to identify gaps in the regulatory framework where existing regulation might not be adequate. We also placed emphasis on the importance of regulators having the necessary expertise.

In our follow-up report, we took the view that it was now high time to move on to agreement on the mechanisms on how to instil what are now commonly accepted ethical principles—I pay tribute to the right reverend Prelate for coming up with the idea in the first place—and to establish national standards for AI development and AI use and application. We referred to the work that was being undertaken by the EU and the Council of Europe, with their risk-based approaches, and also made recommendations focused on development of expertise and better understanding of risk of AI systems by regulators. We highlighted an important advisory role for the Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation and urged that it be placed on a statutory footing.

We welcomed the formation of the Digital Regulation Cooperation Forum. It is clear that all the regulators involved—I apologise for the initials in advance—the ICO, CMA, Ofcom and the FCA, have made great strides in building a centre of excellence in AI and algorithm audit and making this public. However, despite the publication of the National AI Strategy and its commitment to trustworthy AI, we still await the Government’s proposals on AI governance in the forthcoming White Paper.

It seems that the debate within government about whether to have a horizontal or vertical sectoral framework for regulation still continues. However, it seems clear to me, particularly for accountability and transparency, that some horizontality across government, business and society is needed to embed the OECD principles. At the very least, we need to be mindful that the extraterritoriality of the EU AI Act means a level of regulatory conformity will be required and that there is a strong need for standards of impact, as well as risk assessment, audit and monitoring, to be enshrined in regulation to ensure, as techUK urges, that we consider the entire AI lifecycle.

We need to consider particularly what regulation is appropriate for those applications which are genuinely high risk and high impact. I hope that, through the recently created AI standards hub, the Alan Turing Institute will take this forward at pace. All this has been emphasised by the debate on the deployment of live facial recognition technology, the use of biometrics in policing and schools, and the use of AI in criminal justice, recently examined by our own Justice and Home Affairs Committee.

My third heading is government co-ordination and strategy. Throughout our reports we have stressed the need for co-ordination between a very wide range of bodies, including the Office for Artificial Intelligence, the AI Council, the CDEI and the Alan Turing Institute. On our follow-up inquiry, we still believed that more should be done to ensure that this was effective, so we recommended a Cabinet committee which would commission and approve a five-year national AI strategy, as did the AI road map.

In response, the Government did not agree to create a committee but they did commit to the publication of a cross-government national AI strategy. I pay tribute to the Office for AI, in particular its outgoing director Sana Khareghani, for its work on this. The objectives of the strategy are absolutely spot on, and I look forward to seeing the national AI strategy action plan, which it seems will show how cross-government engagement is fostered. However, the Committee on Standards in Public Life—I am delighted that the noble Lord, Lord Evans, will speak today—report on AI and public standards made the deficiencies in common standards in the public sector clear.

Subsequently, we now have an ethics, transparency and accountability framework for automated decision-making in the public sector, and more recently the CDDO-CDEI public sector algorithmic transparency standard, but there appears to be no central and local government compliance mechanism and little transparency in the form of a public register, and the Home Office appears to be still a law unto itself. We have AI procurement guidelines based on the World Economic Forum model but nothing relevant to them in the Procurement Bill, which is being debated as we speak. I believe we still need a government mechanism for co-ordination and compliance at the highest level.

The fourth heading is impact on jobs and skills. Opinions differ over the potential impact of AI but, whatever the chosen prognosis, we said there was little evidence that the Government had taken a really strategic view about this issue and the pressing need for digital upskilling and reskilling. Although the Government agreed that this was critical and cited a number of initiatives, I am not convinced that the pace, scale and ambition of government action really matches the challenge facing many people working in the UK.

The Skills and Post-16 Education Act, with its introduction of a lifelong loan entitlement, is a step in the right direction and I welcome the renewed emphasis on further education and the new institutes of technology. The Government refer to AI apprenticeships, but apprentice levy reform is long overdue. The work of local digital skills partnerships and digital boot camps is welcome, but they are greatly underresourced and only a patchwork. The recent Youth Unemployment Select Committee report Skills for Every Young Person noted the severe lack of digital skills and the need to embed digital education in the curriculum, as did the AI road map. Alongside this, we shared the priority of the AI Council road map for more diversity and inclusion in the AI workforce and wanted to see more progress.

At the less rarefied end, although there are many useful initiatives on foot, not least from techUK and Global Tech Advocates, it is imperative that the Government move much more swiftly and strategically. The All-Party Parliamentary Group on Diversity and Inclusion in STEM recommended in a recent report a STEM diversity decade of action. As mentioned earlier, broader digital literacy is crucial too. We need to learn how to live and work alongside AI.

The fifth heading is the UK as a world leader. It was clear to us that the UK needs to remain attractive to international research talent, and we welcomed the Global Partnership on AI initiative. The Government in response cited the new fast-track visa, but there are still strong concerns about the availability of research visas for entrance to university research programmes. The failure to agree and lack of access to EU Horizon research funding could have a huge impact on our ability to punch our weight internationally.

How the national AI strategy is delivered in terms of increased R&D and innovation funding will be highly significant. Of course, who knows what ARIA may deliver? In my view, key weaknesses remain in the commercialisation and translation of AI R&D. The recent debate on the Science and Technology Committee’s report on catapults reminded us that this aspect is still a work in progress.

Recent Cambridge round tables have confirmed to me that we have a strong R&D base and a growing number of potentially successful spin-outs from universities, with the help of their dedicated investment funds, but when it comes to broader venture capital culture and investment in the later rounds of funding, we are not yet on a par with Silicon Valley in terms of risk appetite. For AI investment, we should now consider something akin to the dedicated film tax credit which has been so successful to date.

Finally, we had, and have, the vexed question of lethal autonomous weapons, which we raised in the original Select Committee report and in the follow-up, particularly in the light of the announcement at the time of the creation of the autonomy development centre in the MoD. Professor Stuart Russell, who has long campaigned on this subject, cogently raised the limitation of these weapons in his second Reith Lecture. In both our reports we said that one of the big disappointments was the lack of definition of “autonomous weapons”. That position subsequently changed, and we were told in the Government’s response to the follow-up report that NATO had agreed a definition of “autonomous” and “automated”, but there is still no comprehensive definition of lethal autonomous weapons, despite evidence that they have clearly already been deployed in theatres such as Libya, and the UK has firmly set its face against laws limitation in international fora such as the CCW.

For a short report, our follow-up report covered a great deal of ground, which I have tried to cover at some speed today. AI lies at the intersection of computer science, moral philosophy, industrial education and regulatory policy, which makes how we approach the risks and opportunities inherent in this technology vital and difficult. The Government are engaged in a great deal of activity. The question, as ever, is whether it is focused enough and whether the objectives, such as achieving trustworthy AI and digital upskilling, are going to be achieved through the actions taken so far. The evidence of success is clearly mixed. Certainly there is still no room for complacency. I very much look forward to hearing the debate today and to what the Minister has to say in response. I beg to move.

Government should use procurement process to secure good work

Recently in the context of its duties under the Procurement Bill I argued for an obligation on Government to ensure that it had regard to the need to secure good work for those carrying out contracts under its procurement activities. This is what I said:

My own interests, and indeed concerns, in this area go back to the House of Lords Select Committee on AI. I chaired this ad hoc inquiry, which produced two reports: AI in the UK: Ready, Willing and Able? and a follow-up report via the Liaison Committee, AI in the UK: No Room for Complacency, which I mentioned in the debate on a previous group.

The issue of the adoption of AI and its relationship to the augmentation of human employment or substitution is key. We were very mindful of the Frey and Osborne predictions in 2013, which estimated that 47% of US jobs are at risk of automation—since watered down—relating to the sheer potential scale of automation over the next few years through the adoption of new technology. The IPPR in 2017 was equally pessimistic. Others, such as the OECD, have been more optimistic about the job-creation potential of these new technologies, but it is notable that the former chief economist of the Bank of England, Andrew Haldane, entered the prediction game not long ago with a rather pessimistic outlook.

Whatever the actual outcome, we said in our report that we need to prepare for major disruption in the workplace. We emphasised that public procurement has a major role in terms of the consequences of AI adoption on jobs and that risk and impact assessments need to be embedded in the tender process.

The noble Lord, Lord Knight, mentioned the All-Party Parliamentary Group on the Future of Work, which, alongside the Institute for the Future of Work, has produced some valuable reports and recommendations in the whole area of the impact of new technology on the workplace. In their reports—the APPG’s The New Frontier and the institute’s Mind the Gap—they recommend that public authorities be obliged to conduct algorithmic impact assessments as a systematic approach to and framework for accountability and as a regulatory tool to enhance the accountability and transparency of algorithmic systems. I tried to introduce in the last Session a Private Member’s Bill that would have obliged public authorities to complete an algorithmic impact assessment where they procure or develop an automated

decision-making system, based on the Canadian directive on artificial intelligence’s impact assessments and the 2022 US Algorithmic Accountability Act.

In particular, we need to consider the consequences for work and working people, as well as the impact of AI on the quality of employment. We also need to ensure that people have the opportunity to reskill and retrain so that they can adapt to the evolving labour market caused by AI. The all-party group said:

“The principles of Good Work should be recognised as fundamental values … to guide development and application of a human-centred AI Strategy. This will ensure that the AI Strategy works to serve the public interest in vision and practice, and that its remit extends to consider the automation of work.”

The Institute for the Future of Work’s Good Work Charter is a useful checklist of AI impacts for risk and impact assessments—for instance, in a workplace context, issues relating to

“access … fair pay … fair conditions … equality … dignity … autonomy … wellbeing … support”

and participation. The noble Lord, Lord Knight, and the noble Baroness, Lady Bennett, have said that these amendments would ensure that impacts on the creation of good, local jobs and other impacts in terms of access to, terms of and quality of work are taken into account in the course of undertaking public procurement.

As the Work Foundation put it in a recent report,

“In many senses, insecure work has become an accepted part of the UK’s labour market over the last 20 years. Successive governments have prioritised raising employment and lowering unemployment, while paying far less attention to the quality and security of the jobs available.”

The Taylor review of modern working practices, Good Work—an independent report commissioned by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy that remains largely unimplemented—concluded that there is a need to provide a framework that better reflects the realities of the modern economy and the spectrum of work carried out.

The Government have failed to legislate to ensure that we do not move even further down the track towards a preponderantly gig economy. It is crucial that they use their procurement muscle to ensure, as in Good Work, that these measures are taken on every major public procurement involving AI and automated decision-making.

Music Touring : The problems remain

The Earl of Clancarty recently initiated a debate on Music Touring. Many of us have been campaigninmg for a number of years to ensure that the huge impact opf Brexit on touring by music artists and other performers and creative creative artists is mitigated.

This what I said:

As we have continuously emphasised in the last two years, we are talking about not only touring by the music industry—one of the most successful and fastest growing sectors, where real jobs and livelihoods now risk being lost—but by a number of other important parts of the creative sector as well: museums, theatre and the wider visual arts sector, as described by the Contemporary Visual Arts Network, and indeed the sports sector, as described by the noble Lord, Lord Moynihan. The ramifications are very broad. The right reverend Prelate reminded us that this impacts on levelling up and on values. We heard from the noble Baroness, Lady Fleet, about the impact on the talent pipeline and the potential to impact on communities through music education.

The dual registration deal on cabotage, which we have debated previously, falls short of satisfying the greater number of smaller specialist hauliers and own-account operators—it was described as a sticking plaster by my noble friend Lord German, and he is correct. On these Benches, we pointed out that the issues on cabotage were just one part of a huge cloud now hanging over the creative sector as a result of Brexit. The noble Viscount, Lord Stansgate, my noble friend Lord Strasburger and the noble Lord, Lord Hannay, all described that, including the requirement for work permits or visa exemptions in many EU countries, CITES certificates for musical instruments, ATA carnets for all instruments and equipment, and proof of origin requirements for merchandise. It is a real return to the past, as described by my noble friend Lord Jones.

The failure to secure a reciprocal exemption to permit freedom of movement for creatives on tour or short-term paid engagements and their support staff when we left the EU has been catastrophic for UK and EU touring creatives. The sheer disparity of treatment was described by my noble friend Lord German. As the noble Lord, Lord Hannay, said, it was very clear from the outset that that would be the impact.

The reason we are in this mess is that the Home Office refused to grant particular categories of EU citizens, including sportspersons or artists performing an activity on an ad hoc basis, the right to 90 days permitted paid engagement, and so the EU would not reciprocate. We are still pursuing freedom of information requests to find out exactly what the UK Government put forward. The problems with merchandise, carnets and CITES are, if anything, worse, as described by a number of noble Lords. As the noble Baroness, Lady Bull, confirmed, the ISM says:

“In fact, almost nothing has changed since the TCA came into effect, as recent accounts from musicians resuming EU tours have demonstrated.”

As the Classical Music APPG, LIVE, UK Music, the ISM and many others have advocated, what is urgently needed are permanent solutions which will secure the kind of future that the noble Viscount, Lord Stansgate, referred to.

Some require bilateral negotiation and some can be done unilaterally through greater engagement, but the key to this is multilateral action. As a number of noble Lords have said, we need more productive, collaborative relationships. This was mentioned by the noble Lords, Lord Hannay and Lord Cormack, my noble friend Lord German and the noble Baroness, Lady Bull. The noble Baroness made some very constructive, detailed suggestions about how we can get to that point on those multilateral negotiations. We need comprehensive negotiation on road haulage for cultural purposes, a cultural waiver in relation to ATA carnets and CITES, and a visa waiver agreement.

There is a very depressing letter from former Minister Lopez to my colleague in the Commons Jamie Stone, which sets out very few constructive proposals. I hope the Minister here today does rather better. Will we get the kind of new beginning that the noble Lord, Lord Cormack, mentioned? We need something simple and effective.

A couple of weeks earlier I had an exchange with Baroness Vere the transport Minister when I asked a question as follows. The Government's response is clearly totally unsatisfactory.

Music Touring

Lord Clement-Jones To ask Her Majesty’s Government, further to their announcement on 6 May regarding “dual registration” for specialist touring hauliers, what assessment they have made of the impact this will have on artists and organisations which tour in their own vehicles and operate under “own account”; and whether they have considered support for smaller hauliers operating which do not have the resources to operate dual registration.

The Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State, Department for Transport

(Baroness Vere of Norbiton) (Con)

My Lords, specialist touring hauliers operating under “own account” can utilise the dual-registration measure if they have a standard international operator licence, which they must apply for, and a base in Great Britain and another country. Operators will need to make their own decisions on whether they choose to do so based on business need and resources available to them.

Lord Clement-Jones (LD)

My Lords, this is all very much half a loaf. If a comprehensive solution is not found, the damage to the UK music industry and the events support industry will be massive. The Prime Minister has assured us that the Government are working “flat out” on the touring issue. Can the Minister assure the House that her department is urgently working on finding a wider solution, such as an exemption from cabotage for all trucks engaged on cultural events?

Baroness Vere of Norbiton

(Con)

Certainly, the department has worked incredibly hard on this and continues to do so. We had a public consultation back in February, and we are deeply engaged with the industry, particularly the specialist haulage industry, which is so important. We know that about one in five hauliers has already set up within the EU, and many more have plans to do so. We recognise that the dual-registration system will not benefit absolutely everybody. However, it is the case under the TCA that many hauliers will be able to make use of their two cross-trades within the bilateral EU-UK movements that they can make. So it does not mean that all touring is off the table. We believe that, at the moment, we have the best possible solution, in light of the current response from the EU.

Lord Clement-Jones

My Lords, is the gist of what the Minister has said today that everything is satisfactory and nothing further needs to be done?

Baroness Vere of Norbiton

I completely reject that—that is not what I am saying at all. The Government absolutely recognise that the measures that we have put in place help the sector and mean that a large proportion of the UK industry can continue to operate, but we acknowledge that not all specialist operators will be in a position to establish a base overseas. As I have said before, our door remains open; we would wish to discuss this with the EU but so far, unfortunately, it has not wanted to do so.

We need to end the confusion and build public trust over health data

During recent debates during the passage of the Health and Scare Bill I helped move amendmendments designed to end the confusion on the use and sharing of Health Data. The complications involved in using health data for public benefit and the lack of public engagement has led to a massive loss of trust. The transfer of health data responsibilities to NHS England from NHS Digital without proper consultation and the GP data opt out fiasco are a particular examples of how public trust can be lost. The review by Profressor Ben Goldacre has recognized this and I hope will lead to a much more comprehensive and clear framework for the protection and use of health data.

The first debate was on the subject of digital transformation of the health service generally

I start by warmly thanking the noble Lord, Lord Hunt of Kings Heath, for allowing me to speak to and lead on this set of amendments, to which his is the leading name. By the same token, I am delighted to see that he is now back in his place and able to advocate much more knowledgeably than I can the merits of the amendments in this group, which relate to the digital aspects of the NHS and the importance of digital transformation in the health service. They are designed to ensure that a digital transformation duty is set out, five-year plans are made, digital issues are high up on the agenda of the ICBs, and progress in this area is assessed and reported on.

I am sorry that I was not able to contribute at Second Reading on digital or data matters. However, as Chris Hopson, chief executive of NHS Providers, said in his Observer piece two Sundays ago,

“we need a national transformation programme that embeds modern technology, 21st century medicine, integrated care closer to home and much greater emphasis on prevention at the heart of our health and care system.”

There is huge potential for technology to help health and care professionals to communicate better and to enable people to access the care they need quickly and easily when it suits them. Quite apart from its impact on planning and administration, the technology, as the NHSE digital transformation website emphasises, goes all the way from ambulance iPads through fitness apps to digital home care technology. It ranges from websites and apps that make care and advice easy to access wherever you are to connected computer systems that give NHS staff the test results, history and evidence they need to make the best decisions for patients.

As the recent Wade-Gery report points out:

“Digital technology is transforming every industry including healthcare. Digital and data have been used to redesign services, raising citizen expectations about self-service, personalisation, and convenience, and increasing workforce productivity.”

It says that the NHS should be in the vanguard. It goes on to say:

“The pandemic has accelerated the shift to online and changed patient expectations and clinical willingness to adopt new ways of working.”

It also says that

“the vaccine programme, supported by so many brilliant volunteers and staff, was only possible through the use of advanced data analytics to drive the risk stratification, population segmentation and operational rollout.”

However, the review also says:

“The need is compelling. The NHS faces unprecedented demand and severe operational pressure as we emerge from the coronavirus pandemic, and we need new ways of working to address this. Now is the moment to put data, digital and technology at the heart of how we transform health services … Effective implementation will require a significant cultural shift away from the current siloed approach in the centre with conscious management to ensure intentions translate to reality … This system leadership should be responsible, in a partnership model between the centre and ICSs, for setting out the business and technology capability requirements of ICSs and the centre with the roadmaps to realise these, and for determining the appropriate high level technical standards, and blueprints for transformed care pathways.”

I have quoted the Wade-Gery review at length but the What Good Looks Like framework set out by NHSX last year is an important document too, designed as it is to be used to accelerate digital and data transformation. It specifies in success measure 1:

“Your ICS has a clear strategy for digital transformation and collaboration. Leaders across the ICS collectively own and drive the digital transformation journey, placing citizens and frontline perspectives at the centre. All leaders promote digitally enabled transformation to efficiently deliver safe, high quality care. Integrated Care Boards (ICBs) build digital and data expertise and accountability into their leadership and governance arrangements, and ensure delivery of the system-wide digital and data strategy.”

Wade-Gery recommends, inter alia, that we

“reorientate the focus of the centre to make digital integral to transforming care”.

In the light of all this, surely that must apply to ICBs as well.

We need to adopt the measures set out in the amendments in this group; namely there should be a director of digital transformation for each ICB. ICBs need clear leadership to devise, develop and deliver the digital transformation that the NHS so badly needs, in line with all the above. There also needs to be a clear duty placed on ICBs to promote digital transformation. It must be included as part of their performance assessment—otherwise, none of this will happen—and in their annual report..

The resources for digital transformation need to be available. Capital expenditure budgets for digital transformation must not be raided for other purposes and digital transformation should take place as planned. It is clear from the Wade-Gery report that we should be doubling and lifting our NHS capital expenditure to 5% of total NHS expenditure, as recommended by the noble Lord, Lord Darzi, and the Institute for Public Policy Research back in June 2018. We should have done that by June 2022 to accord with his recommendations but we are still suffering from chronic underinvestment in digital technology. Indeed, what are the Government’s expenditure plans on NHS digital transformation? We should be ring-fencing the 5% as firmly as we can. As Wade-Gery says:

“NHSEI should therefore as a matter of urgency determine the levels of spend on IT across the wider system and seek to re-prioritise spend from within the wider NHSE budget to support accelerated digital transformation.”

It adds up to asking why these digital transformation aspirations have been put in place without willing the means.

I am also mindful of the other side of the coin of the adoption of digital transformation: there needs to be public information and engagement.

Our amendments are designed to ensure the provision of information about the deployment of treatments and technology as part of ICBs’ patient involvement and patient choice duties. Without that kind of transparency, there will not be the patient and public trust in the NHS adoption of digital technology that is needed. Rightly, success measure 1 of the NHSX What Good Looks Like framework includes that an ICS should, inter alia,

“identify ICS-wide digital and data solutions for improving health and care outcomes by regularly engaging with partners, citizen and front line groups”.

Success measure 5, titled “Empower citizens”, says:

“What does good look like? Citizens are at the centre of service design and have access to a standard set of digital services that suit all literacy and digital inclusion needs. Citizens can access and contribute to their healthcare information, taking an active role in their health and well-being.”

So in the NHS’s view the engagement and provision of information about the deployment of new technologies is absolutely part of the delivery of a digital transformation strategy.

In essence, the amendments would enshrine what is already there in Wade-Gery and best practice guidance where it relates to digital technology and transformation. We should be making sure that our NHS legislation is fully updated in line with that report and with the guidance on what success looks like for the digital age. I hope the Minister agrees to take the amendments on board, and I look forward to hearing his reply.

The second two committee debates were specifically on health data

These amendments relate to the abolition of the Health and Social Care Information Centre and the implications for the integrity of patient data. Clauses 88 and 89 give the Secretary of State powers through regulations to transfer a function from one relevant body to another, and the relevant bodies are defined as Health Education England, the Health and Social Care Information Centre, the Health Research Authority, the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority, the Human Tissue Authority and NHS England. Other than NHS England, each of those bodies can be abolished under the clause as the result of a transfer of functions.

Clause 88 provides for the abolition of the Health and Social Care Information Centre. The Government have announced that they will be using the powers in that clause to merge NHS Digital to form part of the new transformation directorate within NHSE, and of course we have seen that NHSX has now been abolished and the relevant personnel have moved into the transformation directorate. The Health and Social Care Information Centre is an executive non-departmental public body created by statute, usually known by the term “NHS Digital”. This amendment, which would prevent that from happening to the HSCIC, is designed to ensure that NHS Digital continues as an entity to safeguard patient data. The merger of NHS Digital with NHSE risks losing the skills and experience that currently sit within NHS Digital. I have mentioned that NHSX has ceased to exist.

There are two risks for patients. One is that important knowledge and skills will be lost as talented people leave the organisation and time is devoted to the nuts and bolts of making the organisation function rather than on achieving its aims. The other is that the new merged organisation will just be too big and unwieldy to respond in an agile way to major challenges such as workforce planning and digital innovation. If NHSE leaders understand how important these challenges are then they will be able to prioritise them and make them part of the organisation’s core function.

I turn to the functions of the statutory safe havens in relation to Clause 89. Part 9 in Chapter 2 of the Health and Social Care Act 2012 lays out the functions and obligations of what is described as the statutory safe haven for patient data from across the health and social care system required for the production of national statistics and for commissioning, regulatory and research purposes, in addition to supporting patient care. Amendment 228 seeks to keep these statutory protections in place and ensure that NHS England does not take on that responsibility, because of a potential conflict of interest in its role.

The bottom line is that we need to retain NHS Digital’s statutory safe haven functions separate from NHS England. As the BMA has said, it is of the utmost importance to retain a quasi-autonomous body for the purposes of collecting, storing and distributing sensitive patient data—something that would be lost under a merger of NHSD and NHSE.

There is one other major advantage of keeping NHS Digital as the digital safe haven. The statutory safe haven’s legal name is the Health and Social Care Information Centre, so there is some obligation to social care. NHSD has always given some thought to integration, even when there was very little on the social care side to integrate with, and little interest from NHSE in doing that work itself. If it all gets merged into NHSE then how will the obligation to collect social care data continue to exist, since NHSE’s responsibility is to the NHS? If this transfer of functions takes place, who will be responsible for the national collection of social care data? Each bit of the social care world will see NHSE as a different entity from NHS Digital. What are the Government’s joining-up plans in respect of the future governance of this kind of data? I beg to move.

I take this opportunity to come back to the Minister to add a query about the data governance regime which he has described this evening and into which we dipped our toe with the last group of amendments. My noble friend anticipated me in discussing the White Paper, which, in turn, follows from the Data Saves Lives draft strategy. I hope we will have the opportunity to meet the Minister to discuss this further because it is a very complex area.

I want to add to that conversation the fact that we variously have IGARD, CAG and the National Data Guardian for Health and Care—as well as NHS Digital, which we hope will remain separate, but we will come to that shortly. We have all these different bodies, but we need a simple regime which helps us understand, for instance, whether the Minister will say, “Yes, it’s already happening”, to the noble Baroness, Lady McIntosh, or, “No, it’s not going to happen.” I could not tell you the answer to that question in my current state of knowledge about the ability to transfer information across the health service and internationally.

There is a balance to be struck between the established protections and new provisions which might expedite the development of access to new and improved treatments and technologies—but it must be done in a safe way. I hope that, between Committee and Report, the Minister will take the opportunity to ensure that we have all the information we need on plans to perform a so-called reset of or new direction for—or however he might like to describe it—the NHS’s use of our health data.

At Report Stage we made some progress

I thank the Minister for his engagement, both on the Floor of the House and in extensive correspondence. This has been really quite a complicated trail. I feel as though we have been in a maze where we have had to follow a bit of string, finding the way through into data governance in the NHS.

We have had to follow certain key principles, which we all share and which the Minister has expressed, including the protection of privacy, the right of opt-out, the value of health data and, above all, the imperative to retain public trust. Given the importance of the new ICB regime, I very much hope that the Minister will be able to comprehensively answer my noble friend’s questions.

But if we have taken the time to get to this point of really understanding—or beginning to understand—the kind of data governance that the ICBs will be subject to, it raises the question of what future guidance will be in place. I very much hope that the Minister can absolutely give us the assurance that there will be new, clear guidance, along the lines I hope he is going to express in response to my noble friend, as soon as possible, especially given the speeding up of the electronic patient record programme, as my noble friend Lady Brinton said. That is, of course, desirable, but it has to be done in a safe manner.

The Minister in his letter—which the noble Lord, Lord Hunt, addressed in his response—seemed a bit affronted that we should raise the credentials of NHSEI as a holder and protector of NHS data. I would refer to the BMJ letter, which I think came online yesterday, from Kingsley Manning, a former chair of NHS Digital. He really does set it all out. I shall not go into great detail but, for instance, he says that merging NHS Digital with NHSE

“is an important and retrograde step.”

Your Lordships may dispute this, but from where he sat this is important. He said:

“In my experience the general approach of NHS England, including of its clinicians, was that much of the guidance and regulations with respect to the use of patient” data “was seen as unnecessary”. That is a pretty big statement and a fairly damning verdict from the former chair of NHS Digital. I do not think that the Minister can simply remedy the situation by assurances, so I support the amendment in the name of the noble Lord, Lord Hunt, and if it is put to a vote, I very much hope that the House will support it.

Finally, whether or not these amendments are pressed, I hope that the Minister will reconsider whether the Goldacre review should be published before the final version of the new NHS data strategy, Data Saves Lives. I welcome the fact that the Goldacre review is going to deal with information governance, but it is important that we should see that before the final version of Data Saves Lives.

Later when the Bill came back to the Lords but before the Golacre review was published I acknowledged that the Government had promised action

My Lords, briefly, I support the remarks of the noble Lord, Lord Hunt, regarding Motions F and F1. He, assisted by my noble friend Lady Brinton and I, has pursued the question of the future of data governance in the NHS with great determination and persistence. I pay tribute to him and to medConfidential in that respect. I know that the Minister, the noble Lord, Lord Kamall, is equally determined to make sure that data governance in the new structures is designed to secure public trust. I very much hope that he will give the assurances sought by the noble Lord, Lord Hunt.

The key problem we identified early on was the conflict of interest referred to by the noble Lord, Lord Hunt, with NHS England in effect marking its own homework, and those who have data governance responsibility reporting directly to senior managers within the digital transformation directorate. I hope that the assurances to be given by the Minister will set out a clear set of governance duties on transparency of oversight, particularly where NHS England is exercising its own statutory powers internally. I look forward to what the Minister has to say

The Queens Speech 2022: Questioning the Government's Digital Agenda

Shortly after the Queens Speech this year which set out the Government's extensive legislative programme in the field of digital regulation I took part in the Lords debate which responded to the Speech.

My Lords, I shall focus mainly on the Government’s digital proposals. As my noble friend Lady Bonham-Carter, the noble Baroness, Lady Merron, and many other noble Lords have made clear, the media Bill and Channel 4 privatisation will face fierce opposition all around this House. It could not be clearer that the policy towards both Channel 4 and the BBC follows some kind of red wall-driven, anti-woke government agenda that has zero logic. The Up Next White Paper on PSB talks of

“embedding the importance of distinctively British content directly into the existing quota system.”

How does the Minister define “distinctively British content”? Is it whatever the Secretary of State believes it is? As for the Government’s response to the consultation on audience protection standards on VOD services, can the Minister confirm that Ofcom will have the power to assess whether a platform’s own-brand age ratings genuinely take account of the values and expectations of UK families, as the BBFC’s do?

But there are key issues that will need dealing with in the Bill’s passage through Parliament. As we have heard from many noble Lords, the “legal but harmful” provisions are potentially dangerous to freedom of expression, with those harms not being defined in the Bill itself. Similarly, with the lack of definition of children’s harms, it needs to be clear that encouraging self-harm or eating disorders is explicitly addressed on the face of the Bill, as my honourable friend Jamie Stone emphasised on Second Reading. My honourable friend Munira Wilson raised whether the metaverse was covered. Noble Lords may have watched the recent Channel 4 “Dispatches” exposing harms in the metaverse and chat rooms in particular. Without including it in the primary legislation, how can we be sure about this? In addition, the category definitions should be based more on risk than on reach, which would take account of cross-platform activity.

One of the great gaps not filled by the Bill, or the recent Elections Act just passed, is the whole area of misinformation and disinformation which gives rise to threats to our democracy. The Capitol riots of 6 January last year were a wake-up call, along with the danger of Donald Trump returning to Twitter.

The major question is why the draft digital markets, competition and consumer Bill is only a draft Bill in this Session. The DCMS Minister Chris Philp himself said in a letter to the noble Baroness, Lady Stowell—the Chair of the Communications and Digital Committee—dated just this 6 May, that

“urgent action in digital markets is needed to address the dominance of a small number of very powerful tech firms.”

In evidence to the BEIS Select Committee, the former chair of the CMA, the noble Lord, Lord Tyrie, recently stressed the importance of new powers to ensure expeditious execution and to impose interim measures.

Given the concerns shared widely within business about the potential impact on data adequacy with the EU, the idea of getting a Brexit dividend from major amendments to data protection through a data reform Bill is laughable. Maybe some clarification and simplification are needed—but not the wholesale changes canvassed in the Data: A New Direction consultation. Apart from digital ID standards, this is a far lower business priority than reforming competition regulation. A report by the New Economics Foundation made what it said was a “conservative estimate” that if the UK were to lose its adequacy status, it would increase business costs by at least £1.6 billion over the next 10 years. As the report’s author said, that is just the increased compliance costs and does not include estimates of the wider impacts around trade shifting, with UK businesses starting to lose EU customers. In particular, as regards issues relating to automated decision-making, citizens and consumers need more protection, not less.

As regards the Product Security and Telecommunications Infrastructure Bill, we see yet more changes to the Electronic Communications Code, all the result of the Government taking a piecemeal approach to broadband rollout. I do, however, welcome the provisions on security standards for connectable tech products.

Added to a massive programme of Bills, the DCMS has a number of other important issues to resolve: the AI governance White Paper; gambling reform, as mentioned by my noble friend Lord Foster; and much-needed input into IP and performers’ rights reform and protection where design and AI are concerned. I hope the Minister is up for a very long and strenuous haul. Have the Government not clearly bitten off more than the DCMS can chew?

Camera Code of practice: motion to Regret

I recently moved a regret motion that "This House regrets the Surveillance Camera Code of Practice because (1) it does not constitute a legitimate legal or ethical framework for the police’s use of facial recognition technology, and (2) it is incompatible with human rights requirements surrounding such technology." The government continues to resist putting in place a proper legislative framework for collection and use of biometric data and deployment of live facial recognition technology despite the Bridges v South Wales Police case , the conclusions of the Ada Lovelace Institute’s Ryder review and its Countermeasures report and the efforts of many campaigning organisations such as Big Brother Watch and Liberty

My Lords, I have raised the subject of live facial recognition many times in this House and elsewhere, most recently last November, in connection with its deployment in schools. Following an incredibly brief consultation exercise, timed to coincide with the height of the summer holidays last year, the Government laid an updated Surveillance Camera Code of Practice, pursuant to the Protection of Freedoms Act 2012, before both Houses on 16 November last year, which came into effect on 12 January 2022.

The subject matter of this code is of great importance. The last Surveillance Camera Commissioner did a survey shortly before stepping down, and found that there are over 6,000 systems and 80,000 cameras in operation across 183 local authorities. The UK is now the most camera-surveilled country in the western world. According to recently published statistics, London remains the third most surveilled city in the world, with 73 surveillance cameras for every 1,000 people. We are also faced with a rising tide of the use of live facial recognition for surveillance purposes.

Let me briefly give a snapshot of the key arguments why this code is insufficient as a legitimate legal or ethical framework for the police’s use of facial recognition technology and is incompatible with human rights requirements surrounding such technology. The Home Office has explained that changes were made mainly to reflect developments since the code was first published, including changes introduced by legislation such as the Data Protection Act 2018 and those necessitated by the successful appeal of Councillor Ed Bridges in the Court of Appeal judgment on police use of live facial recognition issued in August 2020, which ruled that that South Wales Police’s use of AFR—automated facial recognition—had not in fact been in accordance with the law on several grounds, including in relation to certain convention rights, data protection legislation and the public sector equality duty.

During the fifth day in Committee on the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill last November, the noble Baroness, Lady Williams of Trafford, the Minister, described those who know about the Bridges case as “geeks”. I am afraid that does not minimise its importance to those who want to see proper regulation of live facial recognition. In particular, the Court of Appeal held in Bridges that South Wales Police’s use of facial recognition constituted an unlawful breach of Article 8—the right to privacy—as it was not in accordance with law. Crucially, the Court of Appeal demanded that certain bare minimum safeguards were required for the question of lawfulness to even be considered.

The previous surveillance code of practice failed to provide such a basis. This, the updated version, still fails to meet the necessary standards, as the code allows wide discretion to individual police forces to develop their own policies in respect of facial recognition deployments, including the categories of people included on a watch-list and the criteria used to determine when to deploy. There are but four passing references to facial recognition in the code itself. This scant guidance cannot be considered a suitable regulatory framework for the use of facial recognition.

There is, in fact, no reference to facial recognition in the Protection of Freedoms Act 2012 itself or indeed in any other UK statute. There has been no proper democratic scrutiny over the code and there remains no explicit basis for the use of live facial recognition by police forces in the UK. The forthcoming College of Policing guidance will not satisfy that test either.

There are numerous other threats to human rights that the use of facial recognition technology poses. To the extent that it involves indiscriminately scanning, mapping and checking the identity of every person within the camera’s range—using their deeply sensitive biometric data—LFR is an enormous interference with the right to privacy under Article 8 of the ECHR. A “false match” occurs where someone is stopped following a facial recognition match but is not, in fact, the person included on the watch-list. In the event of a false match, a person attempting to go about their everyday life is subject to an invasive stop and may be required to show identification, account for themselves and even be searched under other police powers. These privacy concerns cannot be addressed by simply requiring the police to delete images captured of passers-by or by improving the accuracy of the technology.

The ECHR requires that any interference with the Article 10 right to freedom of expression or the Article 11 right to free association is in accordance with law and both necessary and proportionate. The use of facial recognition technology can be highly intimidating. If we know our faces are being scanned by police and that we are being monitored when using public spaces, we are more likely to change our behaviour and be influenced on where we go and who we choose to associate with.

Article 14 of the ECHR ensures that no one is denied their rights because of their gender, age, race, religion or beliefs, sexual orientation, disability or any other characteristic. Police use of facial recognition gives rise to two distinct discrimination issues: bias inherent in the technology itself and the use of the technology in a discriminatory way.

Liberty has raised concerns regarding the racial and socioeconomic dimensions of police trial deployments thus far—for example, at Notting Hill Carnival for two years running as well as twice in the London Borough of Newham. The disproportionate use of this technology in communities against which it “underperforms” —according to its proponent’s standards—is deeply concerning.

As regards inherent bias, a range of studies have shown facial recognition technology disproportionately misidentifies women and BAME people, meaning that people from these groups are more likely to be wrongly stopped and questioned by police and to have their images retained as the result of a false match.

The Court of Appeal determined that South Wales Police had failed to meet its public sector equality duty, which requires public bodies and others carrying out public functions to have due regard to the need to eliminate discrimination. The revised code not only fails to provide any practical guidance on the public sector equality duty but, given the inherent bias within facial recognition technology, it also fails to emphasise the rigorous analysis and testing required by the public sector equality duty.

The code itself does not cover anybody other than police and local authorities, in particular Transport for London, central government and private users where there have also been concerning developments in terms of their use of police data. For example, it was revealed that the Trafford Centre in Manchester scanned the faces of every visitor for a six-month period in 2018, using watch-lists provided by Greater Manchester Police—approximately 15 million people. LFR was also used at the privately owned but publicly accessible site around King’s Cross station. Both the Met and British Transport Police had provided images for their use, despite originally denying doing so.

It is clear from the current and potential future human rights impact of facial recognition that this technology has no place on our streets. In a recent opinion, the former Information Commissioner took the view that South Wales Police had not ensured that a fair balance had been struck between the strict necessity of the processing of sensitive data and the rights of individuals.

The breadth of public concern around this issue is growing clearer by the day. Several major cities in the US have banned the use of facial recognition and the European Parliament has called for a ban on police use of facial recognition technology in public places and predictive policing. In response to the Black Lives Matter uprisings in 2020, Microsoft, IBM and Amazon announced that they would cease selling facial recognition technology to US law enforcement bodies. Facebook, aka Meta, also recently announced that it will be shutting down its facial recognition system and deleting the “face prints” of more than a billion people after concerns were raised about the technology.

In summary, it is clear that the Surveillance Camera Code of Practice is an entirely unsuitable framework to address the serious rights risk posed by the use of live facial recognition in public spaces in the UK. As I said in November in the debate on facial recognition technology in schools, the expansion of such tools is a

“short cut to a widespread surveillance state.”—[Official Report, 4/11/21; col. 1404.]

Public trust is crucial. As the Biometrics and Surveillance Camera Commissioner said in a recent blog:

“What we talk about in the end, is how people will need to be able to have trust and confidence in the whole ecosystem of biometrics and surveillance”.

I have on previous occasions, not least through a Private Member’s Bill, called for a moratorium on the use of LFR. In July 2019, the House of Commons Science and Technology Committee published a report entitled The Work of the Biometrics Commissioner and the Forensic Science Regulator. It repeated a call made in an earlier 2018 report that

“automatic facial recognition should not be deployed until concerns over the technology’s effectiveness and potential bias have been fully resolved.”

The much-respected Ada Lovelace Institute has also called for a

“a voluntary moratorium by all those selling and using facial recognition technology”,

which would

“enable a more informed conversation with the public about limitations and appropriate safeguards.”

Rather than update toothless codes of practice to legitimise the use of new technologies like live facial recognition, the UK should have a root and branch surveillance camera review which seeks to increase accountability and protect fundamental rights. The review should investigate the novel rights impacts of these technologies, the scale of surveillance we live under and the regulations and interventions needed to uphold our rights.

We were reminded by the leader of the Opposition on Monday about what Margaret Thatcher said, and I also said this to the Minister earlier this week:

“The first duty of Government is to uphold the law. If it tries to bob and weave and duck around that duty when it’s inconvenient, if Government does that, then so will the governed and then nothing is safe—not home, not liberty, not life itself.”

It is as apposite for this debate as it was for that debate on the immigration data exemption. Is not the Home Office bobbing and weaving and ducking precisely as described by the late Lady Thatcher?

My Lords, I thank the Minister for her comprehensive reply. This has been a short but very focused debate and full of extraordinary experience from around the House. I am extremely grateful to noble Lords for coming and contributing to this debate in the expert way they have.

Some phrases rest in the mind. The noble Lord, Lord Alton, talked about live facial recognition being the tactic of authoritarian regimes, and there are several unanswered questions about Hikvision in particular that he has raised. The noble Lord, Lord Anderson, talked about the police needing democratic licence to operate, which was also the thrust of what the noble Lord, Lord Rosser, has been raising. It was also very telling that the noble Lord, Lord Anderson, said the IPA code was much more comprehensive than this code. That is somewhat extraordinary, given the subject matter of the IPA code. The mantra of not stifling innovation seems to cut across every form of government regulation at the moment. The fact is that, quite often, certainty in regulation can actually boost innovation— I think that is completely lost on this Government.

The noble Baroness, Lady Falkner, talked about human rights being in a parlous state, and I appreciated her remarks—both in a personal capacity and as chair of the Equality and Human Rights Commission—about the public sector equality duty and what is required, and the fact that human rights need to be embedded in the regulation of live facial recognition.

Of course, not all speakers would go as far as I would in asking for a moratorium while we have a review. However, all speakers would go as far as I go in requiring a review. I thought the adumbration by the noble Lord, Lord Rosser, of the elements of a review of that kind was extremely useful.

The Minister spent some time extolling the technology —its accuracy and freedom from bias and so on—but in a sense that is a secondary issue. Of course it is important, but the underpinning of this by a proper legal framework is crucial. Telling us all to wait until we see the College of Policing guidance does not really seem satisfactory. The aspect underlying everything we have all said is that this is piecemeal—it is a patchwork of legislation. You take a little bit from equalities legislation, a little bit from the Data Protection Act, a little bit to come—we know not what—from the College of Policing guidance. None of that is satisfactory. Do we all just have to wait around until the next round of judicial review and the next case against the police demonstrate that the current framework is not adequate?

Of course I will not put this to a vote. This debate was to put down a marker—another marker. The Government cannot be in any doubt at all that there is considerable anxiety and concern about the use of this technology, but this seems to be the modus operandi of the Home Office: do the minimum as required by a court case, argue that it is entirely compliant when it is not and keep blundering on. This is obviously light relief for the Minister compared with the police Bill and the Nationality and Borders Bill, so I will not torture her any further. However, I hope she takes this back to the Home Office and that we come up with a much more satisfactory framework than we have currently.

Live Facial Recognition: Home Office in Denial