Lords Debate Report on AI in Autonomous Weapon Systems

Recently the House of Lords Debated the Report of the Special Inquiry Select Committee into AI in Autonomous Weapon Systems : Proceed with Caution.

This is an edited version of what I said

Autonomous weapon systems present some of the most emotive and high-risk challenges posed by AI. We have heard a very interesting rehearsal of some of the issues surrounding use and possible benefits, but particularly the risks. I believe that the increasing use of drones in particular, potentially autonomously, in conflicts such as Libya, Syria and Ukraine and now by Iran and Israel, together with AI targeting systems such as Lavender, highlights the urgency of addressing the governance of weapon systems.

The implications of autonomous weapons systems—AWS—are far-reaching. There are serious risks to consider, such as escalation and proliferation of conflict, accountability and lack of accountability for actions,

and cybersecurity vulnerabilities. There is the lack of empathy and kindness qualities that humans are capable of in making military decisions. There is misinformation and disinformation, which is a new kind of warfare.

Professor Stuart Russell, in his Reith lecture on this subject in 2021, painted a stark picture of the risks posed by scalable autonomous weapons capable of destruction on a mass scale. This chilling scenario underlines the urgency with which we must approach the regulation of AWS. The UK military sees AI as a priority for the future, with plans to integrate “boots and bots” to quote a senior military officer.

The UK integrated review of 2021 made lofty commitments to ethical AI development. Despite this and the near global consensus on the need to regulate AWS, the UK has not yet endorsed limitations on their use. The UK’s defence AI strategy and its associated policy statement, Ambitious, Safe, Responsible, acknowledged the line that should not be crossed regarding machines making combat decisions but lacked detail on where this line is drawn, raising ethical, legal and indeed moral concerns.

As we explored this complex landscape as a committee—and it was quite a journey for many of us—we found that, while the term AWS is frequently used, its definition is elusive. The inconsistency in how we define and understand AWS has significant implications for the development and governance of these technologies. However, the committee demonstrated that a working definition is possible, distinguishing between fully and partially autonomous systems. This is clearly still resisted by the Government, as their response has shown.

The current lack of definition allows for the assertion that the UK neither possesses nor intends to develop fully autonomous systems, but the deployment of autonomous systems raises questions about accountability, especially in relation to international humanitarian law. The Government emphasise the sufficiency of existing international humanitarian law while a human element in weapon deployment is retained. The Government have consistently stated that UK forces do not use systems that deploy lethal force without human involvement, and I welcome that.

Despite the UK’s reluctance to limit AWS, the UN and other states advocate for specific regulation. The UN Secretary-General, António Guterres, has called autonomous weapons with life-and-death decision-making powers “politically unacceptable, morally repugnant” and deserving of prohibition, yet an international agreement on limitation remains elusive.

In our view, the rapid development and deployment of AWS necessitates regulatory frameworks that address the myriad of challenges posed by these technologies. The relationship between our own military and the private sector makes it even more important that we address the challenges posed by these technologies and ensure compliance with international law to maintain ethical standards and human oversight. I share the optimism of the noble Lord, Lord Holmes, that this is both possible and necessary.

Human rights organisations have urged the UK to lead in establishing new international law on autonomous weapon systems to address the current deadlock in conventional weapons conventions, and we should do so. There is a clear need for the UK to play an active role in shaping the nature of future military engagement.

A historic moment arrived last November with the UN’s first resolution on autonomous weapons, affirming the application of international law to these systems and setting the stage for further discussion at the UN General Assembly. The UK showed support for the UN resolution that begins consultations on these systems, which I very much welcome. The Government have committed also to explicitly ensure human control at all stages of an AWS’s life cycle. It is essential to have human control over the deployment of the system, to ensure both human moral agency and compliance with international humanitarian law.

However, the Government still have a number of questions to answer. Will they respond positively to the call by the UN Secretary-General and the International Committee of the Red Cross that a legally binding instrument be negotiated by states by 2026? How do the Government intend to engage at the Austrian Government’s conference “Humanity at the Crossroads”, which is taking place in Vienna at the end of this month? What is the Government’s assessment of the implications of the use of AI targeting systems under international humanitarian law? Can the Government clarify how new international law on AWS would be a threat to our defence interests? What factors are preventing the Government adopting a definition of AWS, as the noble Lord, Lord Lisvane, asked? What steps are being taken to ensure meaningful human involvement throughout the life cycle of AI-enabled military systems? Finally, will the Government continue discussions at the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons, and continue to build a common understanding of autonomous weapon systems and elements of the constraints that should be placed on them?

The committee rightly warns that time is short for us to tackle the issues surrounding AWS. I hope the Government will pay close and urgent attention to its recommendations.

Lord Holmes Private Members bill a "stake in the ground" says Lord C-J

Lord Holmes of Richmond recently introduced his Private Members Bill -The Artificial Intelligence (Regulation) Bill.

This may not go as far in regulating AI as many want to see but it is a good start. This what Lord Holmes says about it on his own website

https://lordchrisholmes.com/artificial-intelligence-regulation-bill/

and this is what I said at its second reading recently

My Lords, I congratulate the noble Lord, Lord Holmes, on his inspiring introduction and on stimulating such an extraordinarily good and interesting debate.

The excellent House of Lords Library guide to the Bill warns us early on:

“The bill would represent a departure from the UK government’s current approach to the regulation of AI”.

Given the timidity of the Government’s pro-innovation AI White Paper and their response, I would have thought that was very much a “#StepInTheRightDirection”, as the noble Lord, Lord Holmes, might say.

There is clearly a fair wind around the House for the Bill, and I very much hope it progresses and we see the Government adopt it, although I am somewhat pessimistic about that. As we have heard in the debate, there are so many areas where AI is and can potentially be hugely beneficial. However, as many noble Lords have emphasised, it also carries risks, not just of the existential kind, which the Bletchley Park summit seemed to address, but others mentioned by noble Lords today, such as misinformation, disinformation, child sexual abuse, and so on, as well as the whole area of competition—the issue of the power and the asymmetry of these big tech AI systems and the danger of regulatory capture.

It is disappointing that, after a long gestation of national AI policy-making, which started so well back in 2017 with the Hall-Pesenti review, contributed to by our own House of Lords Artificial Intelligence Committee, the Government have ended up by producing a minimalist approach to AI regulation. I liked the phrase used by the noble Lord, Lord Empey, “lost momentum”, because it certainly feels like that after this period of time.

The UK’s National AI Strategy, a 10-year plan for UK investment in and support of AI, was published in September 2021 and accepted that in the UK we needed to prepare for artificial general intelligence. We needed to establish public trust and trustworthy AI, so often mentioned by noble Lords today. The Government had to set an example in their use of AI and to adopt international standards for AI development and use. So far, so good. Then, in the subsequent AI policy paper, AI Action Plan, published in 2022, the Government set out their emerging proposals for regulating AI, in which they committed to develop

“a pro-innovation national position on governing and regulating AI”,

to be set out in a subsequent governance White Paper. The Government proposed several early cross-sectoral and overarching principles that built on the OECD principles on artificial intelligence: ensuring safety, security, transparency, fairness, accountability and the ability to obtain redress.

Again, that is all good, but the subsequent AI governance White Paper in 2023 opted for a “context-specific approach” that distributes responsibility for embedding ethical principles into the regulation of AI systems across several UK sector regulators without giving them any new regulatory powers. I thought the analysis of this by the noble Lord, Lord Young, was interesting. There seemed to be no appreciation that there were gaps between regulators. That approach was confirmed this February in the response to the White Paper consultation.

Although there is an intention to set up a central body of some kind, there is no stated lead regulator, and the various regulators are expected to interpret and apply the principles in their individual sectors in the expectation that they will somehow join the dots between them. There is no recognition that the different forms of AI are technologies that need a comprehensive cross-sectoral approach to ensure that they are transparent,

explainable, accurate and free of bias, whether they are in an existing regulated or unregulated sector. As noble Lords have mentioned, discussing existential risk is one thing, but going on not to regulate is quite another.

Under the current Data Protection and Digital Information Bill, data subject rights regarding automated decision-making—in practice, by AI systems—are being watered down, while our creatives and the creative industries are up in arms about the lack of support from government in asserting their intellectual property rights in the face of the ingestion of their material by generative AI developers. It was a pleasure to hear what the noble Lord, Lord Freyberg, had to say on that.

For me, the cardinal rules are that business needs clarity, certainty and consistency in the regulatory system if it is to develop and adopt AI systems, and we need regulation to mitigate risk to ensure that we have public trust in AI technology. Regulation is not necessarily the enemy of innovation; it can be a stimulus. That is something that we need to take away from this discussion.

This is where the Bill of the noble Lord, Lord Holmes, is an important stake in the ground, as he has described. It provides for a central AI authority that has a duty of looking for gaps in regulation; it sets out extremely well out the safety and ethical principles to be followed; it provides for regulatory sandboxes, which we should not forget are an innovation invented in the UK; and it provides for AI responsible officers and for public engagement. Importantly, it builds in a duty of transparency regarding data and IP-protected material where they are used for training purposes, and for labelling AI-generated material, as the noble Baroness, Lady Stowell, and her committee have advocated. By itself, that would be a major step forward, so, as the noble Lord knows, we on these Benches wish the Bill very well, as do all those with an interest in protecting intellectual property, as we heard the other day at the round table that he convened.

However, in my view what is needed at the end of the day is the approach that the interim report of the Science, Innovation and Technology Committee recommended towards the end of last year in its inquiry into AI governance: a combination of risk-based cross-sectoral regulation and specific regulation in sectors such as financial services, applying to both developers and adopters, underpinned by common trustworthy standards of risk assessment, audit and monitoring. That should also provide recourse and redress, as the Ada Lovelace Institute, which has done so much work in the area, asserts.

That should include the private sector, where there is no effective regulator for the workplace, mentioned, and the public sector, where there is no central or local government compliance mechanism; no transparency yet in the form of a public register of use of automated decision-making, despite the promised adoption of the algorithmic recording standard; and no recognition by the Government that explicit legislation and/or regulation for intrusive

AI technologies used in the public sector, such as live facial recognition and other biometric capture, is needed. Then, of course, we need to meet the IP challenge. We need to introduce personality rights to protect our artists, writers and performers. We need the labelling of AI-generated material alongside the kinds of transparency duties contained in the noble Lord’s Bill.

Then there is another challenge, which is more international. We have world-beating AI researchers and developers. How can we ensure that, despite differing regulatory regimes—for instance, between ourselves and the EU or the US—developers are able to commercialise their products on a global basis and adopters can have the necessary confidence that the AI product meets ethical standards?

The answer, in my view, lies in international agreement on common standards such as those of risk and impact assessment, testing, audit, ethical design for AI systems, and consumer assurance, which incorporate what have become common internationally accepted AI ethics. Having a harmonised approach to standards would help provide the certainty that business needs to develop and invest in the UK more readily, irrespective of the level of obligation to adopt them in different jurisdictions and the necessary public trust. In this respect, the UK has the opportunity to play a much more positive role with the Alan Turing Institute’s AI Standards Hub and the British Standards Institution. The OECD.AI group of experts is heavily involved in a project to find common ground between the various standards.

We need a combination of proportionate but effective regulation in the UK and the development of international standards, so, in the words of the noble Lord, Lord Holmes, why are we not legislating? His Bill is a really good start; let us build on it.

New Digital Markets Bill Must Not be Watered Down

The Digital Markets Competition and Consumer Bill had its Second Reading in the House of Lords on the 5th December 2023 and its 3rd Reading on the 26th March 2024 This is an edited version of what I said on each occasion

Second Reading

I thank the Minister for what I thought was a comprehensive introduction that really set the scene for the Bill. As my noble friend said, we very much welcome the Bill, broadly. It is an overdue offspring of the Furman review and, along with so many noble Lords around the House, he gave very cogent reasons, given the dominance that big tech has and the inadequate powers that our competition regulators have had to tackle them. It is absolutely clear around the House that there is great appetite for improving the Bill. I have knocked around this House for a few years, and I have never heard such a measure of agreement at Second Reading.

We seem to have repeated ourselves, but repetition is good. I am sure that in the Minister’s notebook he just has a list saying “agree, agree, agree” as we have gone through the Bill. I very much hope that he will follow the example that both he and the noble Lord, Lord Parkinson, demonstrated on the then Online Safety Bill and will engage across and around the Chamber with all those intervening today, so that we really can improve the Bill.

It is not just size that matters: we must consider behaviour, dominance, market failure and market power. We need to hold on to that. We need new, flexible pro-competition powers and the ability to act ex ante and on an interim basis—those are crucial powers for the CMA. As we have heard from all round the House, the digital landscape, whether it is app stores, cloud services or more, is dominated by the power of certain big tech companies, particularly in AI, with massive expenditure on compute power, advanced semiconductors, large datasets and the scarce technology skills forming a major barrier to entry where the development of generative AI is concerned. We can already see the future coming towards us.

In that context, I very much welcome Ofcom’s decision to refer the hyperscalers in cloud services for an investigation by the CMA. The CMA and the DMU have the capability to deliver the Bill’s aims.the It must have the ability to implement the new legislative powers. Unlike some other commentators, we believe, as my noble friend said, that the CMA played a positively useful role in the Activision Blizzard-Microsoft merger. It is crucial that the CMA is independent of government. All around the House, there was comment about the new powers of the Secretary of State in terms of guidance. The accountability to Parliament will also be crucial, and that was again a theme that came forward. We heard about the Joint Committee proposals made by both the committee of the noble Baroness, Lady Stowell, and the Joint Committee on the Online Safety Bill.

We need to ensure that that scrutiny is there and, as the Communications and Digital Committee also said, that the DMU is well resourced and communicates its priorities, work programmes and decisions regularly to external stakeholders and Parliament.

The common theme across this debate—to mention individual noble Lords, I would have to mention almost every speaker—has been that the Bill must not be watered down. In many ways, that means going back to the original form of the Bill before it hit Report in the Commons. We certainly very much support that approach, whether it is to do with the merits approach to penalties, the explicit introduction of proportionality or the question of deleting the indispensability test in the countervailing benefits provisions. We believe that, quite apart from coming back on the amendments from Report, the Bill could be further strengthened in a number of respects.

In the light of the recent Open Markets Institute report, we should be asking whether we are going far enough in limiting the power of big tech. In particular, as regards the countervailing benefits exemption, as my noble friend said, using the argument of countervailing benefits—even if we went back to the definition from Report—must not be used by big tech as a major loophole to avoid regulatory action. It is clear that many noble Lords believe, especially in the light of those amendments, that the current countervailing benefits exemption provides SMS firms with too much room to evade conduct requirements.

The key thing that unites us is the fact that, even though we must act in consumers’ interests, this is not about short-term consumer welfare but longer-term consumers’ interests; a number of noble Lords from across the House have made that really important distinction.

We believe that there should be pre-notification if a platform intends to rely on this exemption. The scope of the exemption should also be significantly curtailed to prevent its abuse, in particular by providing an exhaustive list of the types of countervailing benefits that SMS firms are able to claim. We would go further in limiting the way in which the exemption operates.

On strategic market status, one of the main strengths of the Bill is its flexible approach. However, the current five-year period does not account for dynamic digital markets that will not have evidence of the position in the market in five years’ time. We believe that the Bill should be amended so that substantial and entrenched market power is mainly based on past data rather than a forward-looking assessment, and that the latter is restricted to a two-year assessment period. The consultation aspect of this was also raised; there should be much greater rights on the consultation of businesses that are not of strategic market status under the Bill.

A number of noble Lords recognised the need for speed. It is not just a question of making sure that the CMA has the necessary powers; it must be able to move quickly. We believe that the CMA should be given the legal power to secure injunctions under the High Court timetable, enabling it to stop anti-competitive activities in days. This would be in addition to the CMA’s current powers.

We have heard from across the House about the final offer mechanism affecting the news media. We believe that a straightforward levy on big tech platforms, redistributed to smaller journalism enterprises, would be a far more equitable approach. However we need to consider in the context of the Bill the adoption by the CMA of the equivalent to Ofcom’s duty in the Communications Act 2003

“to further the interests of citizens”,

so that it must consider the importance of an informed democracy and a plural media when considering its remedies.

The Bill needs to make it clear that platforms need to pay properly and fairly for content, on benchmarked terms and with reference to value for end-users. Indeed, we believe that they must seek permission for the content that they use. As we heard from a number of noble Lords, that is becoming particularly important as regards the large language models currently being developed.

We also believe it is crucial that smaller publishers are not frozen out or left with small change while the highly profitable large publishers scoop the pool. I hope that we will deal with the Daily Telegraph ownership question and the mergers regime in the Enterprise Act as we go forward into Committee, to make sure that the accumulation of social media platforms is assessed beyond the purely economic perspective. The Enterprise Act powers should be updated to allow the Secretary of State to issue a public interest notice seeking Ofcom’s advice on digital media mergers, as well as newspapers, and at the lower thresholds proposed by this Bill.

There were a number of questions related to leveraging. We want to make sure that we have the right approach to that. The Bill does not seem to be drafted properly in allowing the CMA to prevent SMS firms using their dominance in designated activities to increase their power in non-designated activities. We want to kick the tyres on that.

Of course, there are a great many consumer protection issues here, which a number of noble Lords raised. They include fake reviews and the need for collective action. It is important that we allow collective action not just on competition rights but further, through consumer claims, data abuse claims and so on. We should cap the costs for claimants in the Competition Appeal Tribunal.These issues also include misleading packaging.

Nearly every speaker mentioned subscriptions. I do not think that I need to point out to the Minister the sheer unanimity on this issue. We need to get this right because there is clearly support across the House for making sure that we get the provisions right while protecting the income of charities.

There is a whole host of other issues that we will no doubt discuss in Committee: mid-contract price rises, drip pricing, ticket touting, online scams and reforming ADR. We want to see this Bill and the new competition and consumer powers make a real difference. However, we believe that we can do this only with some key changes being made to the Bill, which are clearly common ground between us all, as we have debated the Bill today. We look forward to the Committee proceedings next year—I can say that now—which will, I hope, be very productive, if both Ministers will it so.

Third Reading

I reiterate the welcome that we on these Benches gave to the Bill at Second Reading. We believe it is vital to tackle the dominance of big tech and to enhance the powers of our competition regulators to tackle it, in particular through the new flexible pro-competition powers and the ability to act ex ante and on an interim basis.

We were of the view, and still are, that the Bill needs strengthening in a number of respects. We have been particularly concerned about the countervailing benefits exemption under Clause 29. This must not be used by big tech as a major loophole to avoid regulatory action. A number of other aspects were inserted into the Bill on Report in the Commons about appeals standards and proportionality. During the passage of the Bill, we added a fourth amendment to ensure that the Secretary of State’s power to approve CMA guidance will not unduly delay the regime coming into effect.

As the noble Baroness, Lady Stowell, said, we are already seeing big tech take an aggressive approach to the EU Digital Markets Act. We therefore believe the Bill needs to be more robust in this respect. In this light, it is essential to retain the four key amendments passed on Report and that they are not reversed through ping-pong when the Bill returns to the Commons.

I thank both Ministers and the Bill team. They have shown great flexibility in a number of other areas, such as online trading standards powers, fake reviews, drip pricing, litigation, funding, cooling-off periods, subscriptions and, above all, press ownership, as we have seen today. They have been assiduous in their correspondence throughout the passage of the Bill, and I thank them very much for that, but in the crucial area of digital markets we have seen no signs of movement. This is regrettable and gives the impression that the Government are unwilling to move because of pressure from big tech. If the Government want to dispel that impression, they should agree with these amendments, which passed with such strong cross-party support on Report.

In closing, I thank a number of outside organisations that have been so helpful during the passage of the Bill—in particular, the Coalition for App Fairness, the Public Interest News Foundation, Which?, Preiskel & Co, Foxglove, the Open Markets Institute and the News Media Association. I also thank Sarah Pughe and Mohamed-Ali Souidi in our own Whips’ Office.

Given the coalition of interest that has been steadily building across the House during the debates on the Online Safety Bill and now this Bill, I thank all noble Lords on other Benches who have made common cause and, consequently, had such a positive impact on the passage of this Bill. As with the Online Safety Act, this has been a real collaborative effort in a very complex area.

Living with the Algorithm now published!

Living with the Algorithm

Servant or Master?

AI Governance and Policy for the Future

Tim Clement-Jones

Published March 2024

Paperback with flaps, £14.99 ISBN: 9781911397922

A comprehensive breakdown of the AI risks and how to address them.

The rapid proliferation of AI brings with it a potentially massive shift in how society interacts with the digital world. New opportunities and challenges are emerging in unprecedented fashion and speed. AI however, comes with its own risks, including the potential for bias and discrimination, reputational harm, and the potential for widescale redundancy of millions of jobs. Many prominent technologists have voiced their concern at the existential risks to humanity that AI pose. So how do we ensure that AI remains our servant and not our master?

The purpose in this book is to identify and address these key risks looking at current approaches to regulation and governance of AI internationally in both the public and private sector, how we meet and mitigate these challenges, avoid inadequate or ill considered regulatory approaches, and protect ourselves from the unforeseen consequences that could flow from unregulated AI development and adoption.

AI Regulation-It's All about Standards

I recently gave a talk to the Engineers' Association of my Alma Mater, Trinity College Cambridge. This is what I said

Video here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2Wnf97_Zu5E

You may ask how and why I have been sucked into the world of AI. Well, 8 years ago I set up a cross-party group in the UK parliament because i thought parliamentarians didn’t know enough about it and then- based on, in the Kingdom of the Blind the fact that one eyed man is king- I was asked to chair the House of Lords Special Enquiry Select Committee on AI with the remit “to consider the economic, ethical and social implications of advances in artificial intelligence. This produced its report “AI in the UK: Ready Willing and Able?” in April 2018. It took a close look at government policy towards AI and its ambitions in the very early days of its policy-making when the UK was definitely ahead of the pack.

Since then I have been lucky enough to have acted as an adviser to the Council of Europe’s working party on AI (CAHAI) the One AI Group of OECD AI Experts and helped establish the OECD Global Parliamentary Network on AI which helps in tracking developments in AI and the policy responses to it, which come thick and fast.

Artificial Intelligence presents opportunities in a whole variety of sectors. I am an enthusiast for the technology -the opportunities for AI are incredibly varied-and I recently wote an upbeat piece on the way that AI is already transforming healthcare.

Many people find it unhelpful to have such a variety of different types of machine learning, algorithms, neural networks, or deep learning, labelled AI. But the expression has been been used since John McCarthy invented it in 1956 and I think we are stuck with it!

Nowadays barely a day goes by without some reference to AI in the news media-particularly some aspect of Large Language Models in the news. We saw the excitement over ChatGPT from Open AI and AI text to image applications such as DALL E and now we have GPT 4 from OpenAI, LlaMa from Meta, Claude from Anthropic, Gemini from Google, Stability Diffusion from Stability AI, Co-pilot from Microsoft, Cohere, Midjourney, -a whole eco system of LLM’s of various kinds.

Increasingly the benefits are not just seen around increasing efficiency, speed etc in terms of analysis, pattern detection and ability to predict but now, with generative AI much more about what creatively AI can add to human endeavour , how it can augment what we do.

But things can go wrong. This isn’t just any old technology.The degree of autonomy, its very versatility, its ability to create convincing fakes, lack of human intervention, the Black box nature of some systems makes it different from other tech. The challenge is to ensure that AI is our servant not our master especially before the advent of AGI.

Failure to tackle issues such as bias/discrimination, deepfakery and disinformation, and lack of transparency will lead to a lack of public/consumer trust, reputational damage and inability to deploy new technology. Public trust and trustworthy AI is fundamental to continued advances in technology.

It is clear that AI even in its narrow form will and should have a profound impact on and implications for corporate governance in terms of the need to ensure responsible or ethical AI adoption.The AI Safety Conference at Bletchley Park-where incidentally my parents met- ended with a voluntary corporate pledge.

This means a more value driven approach to the adoption of new technology needs to be taken. Engagement from boards through governance right through to policy implementation is crucial. This is not purely a matter that can be delegated to the CTO or CIO.

It means in particular assessing the ethics of adoption of AI and the ethical standards to be applied corporately : It may involve the establishment of an ethics advisory committee.It certainly involves clear Board accountability..

We have a pretty good common set of principles -OECD or G20- which are generally regarded as the gold standard which can be adopted which can help us ensure

- Quality of training data

- Freedom from Bias

- The impact on Individual civil and human rights

- Accuracy and robustness

- Transparency and Explainability which of course include the need for open communication where these technologies are deployed.

And now we have the G7 principles for Organizations Developing Advanced AI systems to back those up.

Generally in business and in the tech research and development world I think there is an appetite for adoption of common standards which incorporate ethical principles such as for

- Risk management

- Impact assessment

- Testing

- AI audit

- Continuous Monitoring

And I am optimistic that common standards can be achieved internationally in all these areas. The OECD Internationally is doing a great deal to scope the opportunity and enable convergence. Our own AI Standards Hub run by the Alan Turing institute is heavily involved. As is NIST in the US and the EU’s CEN-CENELEC standards bodies too.

Agreement on the actual regulation of AI in terms of what elements of governance and application of standards should be mandatory or obligatory, however, is much more difficult.

In the UK there are already some elements of a legal framework in place. Even without specific legislation, AI deployment in the UK will interface with existing legislation and regulation in particular relating to

- Personal data under UK GDPR

- Discrimination and unfair treatment under the Human Rights Act and Equality Act

- Product safety and public safety legislation

- And various sector-specific regulatory regimes requiring oversight and control by persons undertaking regulated functions, the FCA for financial services, Ofcom in the future for social media for example.

But when it comes to legislation and regulation that is specific to AI such over transparency and explanation and liability that’s where some of the difficulties and disagreements start emerging especially given the UK’s approach in its recent White Paper and the government’s response to the consultation.

Rather than regulating in the face of clear current evidence of the risk of the many uses and forms of AI it says it’s all too early to think about tackling the clear risks in front of us. More research is needed. We are expected to wait until we have complete understanding and experience of the risks involved. Effectively in my view we are being treated as guinea pigs to see what happens whilst the government talks about the existential risks of AGI instead.

And we shouldn’t just focus on existential long term risk or indeed risk from Frontier AI, predictive AI is important too in terms of automated decision making, risk of bias and lack of transparency.

The government says it wishes its regulation to be innovation friendly and context specific but sticking to their piecemeal context specific approach the government are not suggesting immediate regulation nor any new powers for sector regulators

But regulation is not necessarily the enemy of innovation, it can in fact be the stimulus and be the key to gaining and retaining public trust around digital technology and its adoption so we can realise the benefits and minimise the risks.

The recent response to the AI White paper has demonstrated the gulf between the government’s rhetoric about being world leading in safe AI.

In my view we need a broad definition of AI and early risk based overarching horizontal legislation across the sectors ensuring that there is conformity with standards for a proper risk management framework and impact assessment when AI systems are developed and aded.

Depending on the extent of the risk and impact assessed, further regulatory requirements would arise. When the system is assessed as high risk there would be additional requirements to adopt standards of testing, transparency and independent audit.

What else is on my wish list? As regards its use of AI and automated decision making systems the government needs to firmly implant its the Algorithmic Transparency Recording Standard alongside risk assessment together with a public register of AI systems in use in government.

It also needs need to beef up the Data Protection Bill in terms of rights of data subjects relative to Automated Decision Making rather than water them down and retain and extend the Data Protection Impact Assessment and DPO for use in AI regulation.

I also hope the Gov will take strong note of the House of Lords report on the use of copyrighted works by LLM’s. The government has adopted its usual approach of relying on a voluntary approach. But it is clear that this is simply is not going to work. It needs to act decisively to make sure that these works are not ingested into training LLM’s without any return to rightsholders.

Luckily others such as the EU-and even the US- contrary to many forecasts are grasping the nettle. The EU’s AI Act is an attempt to grapple with the here and now risks in a constructive way and even the US where the White House Executive Order and Congressional bi-partisan proposals show a much more proactive approach.

But the more we diverge when it comes to regulation from other jurisdictions the more difficult it gets for UK developers and those who want to develop AI systems internationally.

International harmonization, interoperability or convergence, call it what you like, is in my view essential if we are to see developers able to commercialize their products on a global basis, assured that they are adhering to common ethical standards of regulation.This means working with the BSI ISO OECD and others towards convergence of international standards.There are already several existing standards such as ISO 42001 and 42006 and NIST’s RMF which can form the basis for this

What I have suggested I believe would help provide the certainty, convergence and consistency we need to develop and invest in responsible AI innovation in the UK more readily. That in my view is the way to get real traction!

Great prospects but ….. The potential and challenges for AI in healthcare.

I recently wrote a piece on AI in healthcare for the Journal of the Apothecaries Livery Company, which has among its membership a great many doctors and health specialists. This is what I said.

In our House of Lords AI Select Committee report “AI in the UK: Ready Willing and Able?” back in 2018, reflecting the views of many of our witnesses about its likely profound impact, we devoted a full chapter to the potential for AI in its application to healthcare. Not long afterwards the Royal College of Physicians itself made several far-sighted recommendations relating to the incentives, scrutiny and regulation needed for AI development and adoption.2

At that time it was already clear that medical imaging and supporting administrative roles were key areas for adoption. Fast forward 5 years to the current enquiry- “Future Cancer-exploring innovations in cancer diagnosis and treatment”- by the House of Commons Health and Social Care Select Committee and the application of different forms of AI is very much already here and now in the NHS.

It is evident that this is a highly versatile technology. The Committee heard in particular from GRAIL Bio UK about its Galleri AI application which has the ability to detect a genetic signal that is shared by over 50 different types of incipient cancer, particularly more aggressive tumours.3 Over the past year, we have heard of other major breakthroughs —tripling stroke recovery rates with Brainomix4, mental health support through the conversational AI application Wysa5 and Eye2Gene a decision support system with genetic diagnosis of inherited retinal disease, and applications for remotely managing conditions at home.6 Mendelian has developed an AI tool, piloting in the NHS, to interrogate large volumes of electronic patient records to find people with symptoms that could be indicative of a rare disease.6A

We have seen the introduction of Frontier software designed to ease bed blocking by improving the patient discharge process.7 And just a few weeks ago we heard of how, using AI, Lausanne researchers have created a digital bridge from the brain and implanted spine electrodes which allow patients with spinal injuries to regain coordination and movement.8 It is also clear despite the recent fate of Babylon Health 9 that consumer AI-enabled health apps and devices can have a strong future too in terms of health monitoring and self-care. We now have large language models such as Med-PaLM developed by Google research which are designed to designed to provide high quality answers to medical questions. 9A

We are seeing the promise of the use of AI in training surgeons for more precise keyhole brain surgery.

Now it seems just around the corner could be foundation models for generalist medical artificial intelligence which are trained on massive, diverse datasets and will be able to perform a very wide range of tasks based on a broad range of data such as images, electronic health records, laboratory results, genomics, graphs or medical text and to provide communicate directly with patients. 10

We even have the promise of Smartphones being able to detect the onset of dementia 10A

Encouragingly—whatever one’s view of the current condition more broadly of the Health Service—successive Secretaries of State for Health have been aware of the potential and have responded by investing. Over the past few years, the Department of Health and the NHS have set up a number of mechanisms and structures designed to exploit and incentivize the development of AI technologies. The pandemic, whilst diminishing treatment capacity in many areas, has also demonstrated that the NHS is capable of innovation and agile adoption of new technology.

Its performance has yet to be evaluated, but through the NHS AI Lab set up in 2019 11, designed to accelerate the safe, ethical and effective adoption of AI in health and social care, with its AI in Health and Care Awards over the past few years, some £123 million has been invested in 86 different AI technologies, including stroke diagnosis, cancer screening, cardiovascular monitoring, mental health, osteoporosis detection, early warning and clinician support tools for obstetrics applications for remotely managing conditions at home. 11

This June the Government announced a new £21 million AI Diagnostic Fund to accelerate deployment of the most promising AI decision support tools in all 5 stroke networks covering 37 hospitals by the end of 2023, given results showing more patients being treated, more efficient and faster pathways to treatment and better patient outcomes.12

In the wider life sciences research field—which our original Lords enquiry dwelt on less—there has been ground-breaking research work by DeepMind in its Alphafold discovery of protein structures13 and Insilico Medicine’s use of generative AI for drug discovery in the field of idiopathic pulmonary treatment which it claims saved 2 years in the route to market.14 GSK has developed a large language model Cerebras to analyse the data from genetic databases which it means can take a more predictive approach in drug discovery .15

Despite these developments as many clinicians and researchers have emphasized—not least recently to the Health and Social Care Committee—the rate of adoption of AI is still too slow.

There are a variety of systemic issues in the NHS which still need to be overcome. We lag far behind health systems such as Israel’s, pioneers of the virtual hospital16, and Estonia.17

The recent NHS Long Term Workforce Plan 18 rightly acknowledges that AI in augmenting human clinicians will be able to greatly relieve pressures on our Health Service, but one of the principal barriers is a lack of skills to exploit and procure the new technologies, especially in working alongside AI systems. As recognized by the Plan, the introduction of AI into potentially so many healthcare settings has huge implications for healthcare professions especially in terms of the need to strike a balance between AI assistance/human augmentation and substitution with all its implications for future deskilling.

Addressing this in itself is a digital challenge that the NHS Digital Academy—a virtual academy set up in 2018 19- was designed to solve. These issues were tackled by the Topol Review “Preparing the Healthcare Workforce to Deliver the Digital Future”, instituted by Jeremy Hunt when Health Secretary, and reported in February 2019 20. Above all, it concluded that NHS organisations will need to develop an expansive learning environment and flexible ways of working that encourage a culture of innovation and learning. Similarly the review by Sir Paul Nurse of the research, development and innovation organisational landscape 21 highlighted a skills and training gap across these different areas and siloed working. The current reality on the ground however is that the adoption of AI and digital technology still does not feature in workforce planning and is not reflected in medical training which is very traditional in its approach.

More specific AI-related skills are being delivered through the AI Centre for Value-based Healthcare. This is led by King’s College London and Guy's and Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, alongside a number of NHS Trusts, Universities and UK and multinational industry partners.22 Funded by grants from UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) and the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) and the Office of Life Sciences their Fellowship in Clinical AI is a year-long programme integrated part-time alongside the clinical training of doctors and dentists approaching consultancy. This was first piloted in London and the South East in 2022 and is now being rolled out more widely but although it has been a catalyst for collaboration it has yet to make an impact at any scale. The fact remains that outside the major health centres there is still insufficient financial or administrative support for innovation.

Set against these ambitions many NHS clinicians complain that the IT in the health service is simply not fit for purpose. This particularly applies in areas such as breast cancer screening.

One of the key areas where developers and adopters can also find frustrations is in the multiplicity of regulators and regulatory processes. Reports such as the review by Professor Dame Angela McLean the Government's Chief Scientific Adviser on the Pro Innovation Regulation of Technologies-Life Sciences 23 identified blockages in the regulatory process for the “innovation pathway”. At the same time however we need to be mindful of the patient safety findings— shocking it must be said—of the Cumberledge Review—the independent Medicines and Medical Device Safety Review.24

To streamline the AI regulatory process the NHS AI Lab has set up the AI and Digital Regulations Service (formerly the multi-agency advisory service) which is a collaboration between 4 regulators: The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, The Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (the MHRA), The Health Research Authority and The Care Quality Commission.25

The MHRA itself through its Software and AI as a Medical Device Change Programme Roadmap is a good example of how an individual health regulator is gearing up for the AI regulatory future, the intention being to produce guidance in a variety of areas, including bringing clarity to distinctions such as software as a medical device versus wellbeing and lifestyle software products and versus medicines and companion diagnostics.26

Specific regulation for AI systems is another factor that healthcare AI developers and adopters will need to factor in going forward. There are no current specific proposals in the UK but the EU’s AI Act will set up a regulatory regime which will apply to high-risk AI systems and applications which are made available within the EU, used within the EU or whose output affects people in the EU.

Whatever regulatory regime applies the higher the impact on the patient an AI application has, the stronger the need for clear and continuing ethical governance to ensure trust in its use, including preventing potential bias, ensuring explainability, accuracy, privacy, cybersecurity, and reliability, and determining how much human oversight should be maintained. This becomes of even greater importance in the long term if AI systems in healthcare become more autonomous.27

In particular AI in healthcare will not be successfully deployed unless the public is confident that its health data will be used in an ethical manner, is of high quality, assigned its true value, and used for the greater benefit of UK healthcare. The Ada Lovelace Institute in conjunction with the NHS AI Lab, has developed an algorithmic impact assessment for data access in a healthcare environment which demonstrates the crucial risk and ethical factors that need to be considered in the context of AI development and adoption .28

For consumer self-care products explainability statements, of the kind developed by Best Practice AI for Heathily’s AI smart symptom checker, which provides a non-technical explanation of the app to its customers, regulators and the wider public will need to become the norm.29 We have also just recently seen the Introduction of British Standard 30440 designed as a validation framework for the use of AI in healthcare 30, All these are steps in the right direction but there needs to be regulatory incentivisation of adoption and compliance with these standards if the technology is to be trustworthy and patients to be safe.

The adoption of and alignment with global standards is a governance requirement of growing relevance too. The WHO in 2021 produced important guidance on the Governance of Artificial Intelligence for Health31

Issues relating to patient data access, which is so crucial for research and training of AI systems, in terms of public trust, procedures for sharing and access have long bedevilled progress on AI development. This was recognized in the Data Saves Lives strategy of 2022 32 and led to the Goldacre Review which reported earlier this year. 33

As a result, greater interoperability and a Federated Data Platform comprised of Secure Research Environments is now emerging with greater clarity on data governance requirements which will allow researchers to navigate access to data more easily whilst safeguarding patient confidentiality.

All this links to barriers to the ability of researchers and developers to conduct clinical trials which has been recognized as a major impediment to innovation. The UK has fallen behind in global research rankings as a result. The O’Shaughnessy review on clinical trials which reported earlier this year made a number of key recommendations 34

-A national participatory process on patient consent to examine how to achieve greater data usage for research in a way that commands public trust. Much greater public communication and engagement on this has long been called for by the National Data Guardian.

-Urgent publication of guidance for NHS bodies on engaging in research with industry. This is particularly welcome. At the time of our Lords report, the Royal Free was criticized by the Information Commissioner for its arrangement with DeepMind which developed its Streams app to diagnose acute kidney injury, as being in breach of data protection law,35 Given subsequent questionable commercial relationships which have been entered into by NHS bodies, a standard protocol for the use of NHS patient data for commercial purposes, ensuring benefit flows back into the health service has long been needed and is only just now emerging.

-Above all, it recommended a much-needed national directory of clinical trials to give much greater visibility to national trials activity for the benefit of patients, clinicians, researchers and potential trial sponsors.

Following the Health and Care Act of 2022, the impact of the recent reorganisation and merger of NHS X and NHS Digital into the Transformation Directorate of NHS England, the former of which was specifically designed when set up in 2019 to speed up innovation and technology adoption in the NHS, is yet to be seen, but clearly, there is an ambition for the new structure to be more effective in driving innovation.

The pace of drug discovery through AI has undoubtedly quickened over recent years but there is a risky and rocky road in the AI healthcare investment environment. Adopting AI techniques for drug discovery does not necessarily shortcut the uncertainties. The experience of drug discovery investor Benevolent AI is a case in point which recently announced that it would need to shed up to 180 staff out of 360.36

Pharma companies are adamant too that in the UK the NHS branded drug pricing system is a disincentive to drug development although it remains to be seen what the newly negotiated voluntary and statutory agreements will deliver.

To conclude, expectations of AI in healthcare are high but where is the next real frontier and where should we be focusing our research and development efforts for maximum impact? Where are the gaps in adoption?

It is still the case that much unrealized AI potential lies in some of the non-clinical healthcare aspects such as workforce planning and mapping demand to future needs. This needs to be allied with day to day clinical AI predictive tools for patient care which can link data sets and combine analysis from imaging and patient records.

In my view too, of even greater significance than improvements in diagnosis and treatment, is a new emphasis on a preventative philosophy through the application of predictive AI systems to genetic data. As a result, long term risks can be identified and appropriate action taken to inform patients and clinicians about the likelihood of their getting a particular disease including common cancer types.

Our Future Health is a new such project working in association with the NHS. 37 The plan (probably overambitious and not without controversy in terms of its intention to link into government non health data) is to collect the vital health statistics of 5 million adult volunteers.

With positive results from this kind of genetic work, however, AI in primary care could come into its own, capturing the potential for illness and disease at a much earlier stage. This is where I believe that ultimately the greatest potential arises for impact on our national health and the opportunity for greater equity in life expectancy across our population lies. Alongside this, however, the greatest care needs to be taken in retaining public trust about personal data access and use and the ethics of AI systems used.

Footnotes

1.AI in the UK : Ready Willing and Able? House of Lords AI Select Committee 2018 Artificial Intelligence Committee - Summary

2. Royal College of Physicians, Artificial intelligence in healthcare Report of a working party, https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/artificial-intelligence-ai-health

3. House of Commons Health and Social Care Committee, Future cancer - Committees

4. Brainomix’s e-Stroke Software Triples Stroke Recovery Rates,https://www.brainomix.com/news/oahsn-interim-report/

5. Evidence-based Conversational AI for Mental Health Wysa

6A https://www.newstatesman.com/spotlight/healthcare/innovation/2023/10/ai-diagnosis-technology-artificial-intelligence-healthcare

7.AI cure for bed blocking can predict hospital stay

8.Clinical trial evaluates implanted tech that wirelessly stimulates spinal cord to restore movement after paralysis, Walking naturally after spinal cord injury using a brain–spine interface

9.Babylon the future of the NHS, goes into administration

9A https://sites.research.google/med-palm/

10. Foundation models for generalist medical artificial intelligence | Nature

10 A. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/ai-could-detect-dementia-long-before-doctors-claims-oxford-professor-slbdz70v3#:~:text=Michael%20Wooldridge%2C%20a%20professor%20of,possible%20sign%20of%20the%20condition.

11..The Artificial Intelligence in Health and Care Award - NHS AI Lab programmes

12.NHS invests £21 million to expand life-saving stroke care app, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/21-million-to-roll-out-artificial-intelligence-across-the-nhs

13.DeepMind, AlphaFold: a solution to a 50-year-old grand challenge in biology, 2020. AlphaFold: a solution to a 50-year-old grand challenge in biology

14.From Start to Phase 1 in 30 Months | Insilico Medicine

15.GlaxoSmithKline and Cerebras are Advancing the State of the Art in AI for Drug Discoveryl

16.Israeli virtual hospital is caring for Ukrainian refugees - ISRAEL21c

17. Estonia embraces new AI-based services in healthcare.

18. NHS Long Term Workforce Plan

20. The Topol Review: Preparing the Healthcare Workforce to Deliver the Digital Future

21.The Nurse Review: Research, development and innovation (RDI) organisational landscape: an independent review - GOV.UK

22. The AI Centre for Value Based Healthcare

23 Pro-innovation Regulation of Technologies Review Life Sciences - GOV.UK

24 Department of Health and Social Care, First Do No Harm – The report of the Independent Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Review, 2020. The report of the IMMDSReview

25. AI and digital regulations service - AI Regulation - NHS Transformation Directorate

26. Software and AI as a Medical Device Change Programme - Roadmap - GOV.UK

27. AI Act: a step closer to the first rules on Artificial Intelligence | News | European Parliament

28. Algorithmic impact assessment in healthcare | Ada Lovelace Institute

31. Ethics and governance of artificial intelligence for health

32. Data saves lives: reshaping health and social care with data - GOV.UK

33. Goldacre Review

34. Commercial clinical trials in the UK: the Lord O’Shaughnessy review - final report - GOV.UK

35 .Royal Free breached UK data law in 1.6m patient deal with Google's DeepMind.

36. BenevolentAI cuts half of its staff after drug trial flop

Lord C-J calls for action on AI regulation and data rights in Kings Speech Debate

I want to start on a positive note by celebrating the recent Royal Assent of the Online Safety Act and the publication of the first draft code for consultation. I also very much welcome that we now have a dedicated science and technology department in the form of DSIT, although I very much regret the loss of Minister George Freeman yesterday.

Sadly, there are many other less positive aspects to mention. Given the Question on AI regulation today, all I will say is that despite all the hype surrounding the summit, including the PM’s rather bizarre interview with Mr Musk, in reality the Government are giving minimal attention to AI, despite the Secretary of State saying that the world is standing at the inflection point of a technological revolution. Where are we on adjusting ourselves to the kinds of risk that AI represents? Is it not clear that the Science, Innovation and Technology Committee is correct in recommending in its interim report that the Government

“accelerate, not … pause, the establishment of a governance regime for AI, including whatever statutory measures as may be needed”?

That is an excellent recommendation.

I also very much welcome that we are rejoining Horizon, but there was no mention in the Minister’s speech of how we will meet the challenge of getting international research co-operation back to where it was. I am disappointed that the Minister did not give us a progress update on the department’s 10 objectives in its framework for science and technology, and on action on the recommendations of its many reviews, such as the Nurse review. Where are the measurable targets and key outcomes in priority areas that have been called for?

Nor, as we have heard, has there been any mention of progress on Project Gigabit, and no mention either of progress on the new programmes to be undertaken by ARIA. There was no mention of urgent action to mitigate increases to visa fees planned from next year, which the Royal Society has described as “disproportionate” and a “punitive tax on talent”, with top researchers coming to the UK facing costs up to 10 times higher than in other leading science nations. There was no mention of the need for diversity in science and technology. What are we to make of the Secretary of State demanding that UKRI “immediately” close its advisory group on EDI? What progress, too, on life sciences policy? The voluntary and statutory pricing schemes for new medicines currently under consultation are becoming a major impediment to future life sciences investment in the UK.

Additionally, health devices suffer from a lack of development and commercialisation incentives. The UK has a number of existing funding and reimbursement systems, but none is tailored for digital health, which results in national reimbursement. What can DSIT do to encourage investment and innovation in this very important field?

On cybersecurity, the G7 recognises that red teaming, or what is called threat-led penetration testing, is now crucial in identifying vulnerabilities in AI systems. Sir Patrick Vallance’s Pro-innovation Regulation of Technologies Review of March this year recommended amending the Computer Misuse Act 1990 to include a statutory public interest defence that would provide stronger legal protections for cybersecurity researchers and professionals carrying out threat intelligence research. Yet there is still no concrete proposal. This is glacial progress.

However, we on these Benches welcome the Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Bill. New flexible, pro-competition powers, and the ability to act ex ante and on an interim basis, are crucial. We have already seen the impact on our sovereign cloud capacity through concentration in just two or three US hands. Is this the future of AI, given that these large language models now developed by the likes of OpenAI, Microsoft, Anthropic AI, Google and Meta require massive datasets, vast computing power, advanced semiconductors, and scarce digital and data skills?

As the Lords Communications and Digital Committee has said, which I very much welcome, the Bill must not, however, be watered down in a way that allows big tech to endlessly challenge the regulators in court and incentivise big tech firms to take an adversarial approach to the regulators. In fact, it needs strengthening in a number of respects. In particular, big tech must not be able to use countervailing benefits as a major loophole to avoid regulatory action. Content needs to be properly compensated by the tech platforms. The Bill needs to make clear that platforms profit from content and need to pay properly and fairly on benchmarked terms and with reference to value for end users. Can the Minister, in winding up, confirm at the very least that the Government will not water down the Bill?

We welcome the CMA’s market investigation into cloud services, but it must look broadly at the anti-competitive practices of the service providers, such as vendor lock-in tactics and non-competitive procurement. Competition is important in the provision of broadband services too. Investors in alternative providers to the incumbents need reassurance that their investment is going on to a level playing field and not one tilted in favour of the incumbents. Can the Minister reaffirm the Government’s commitment to infrastructure competition in the UK telecommunications industry?

The Data Protection and Digital Information Bill is another matter. I believe the Government are clouded by the desire to diverge from the EU to get some kind of Brexit dividend. The Bill seems largely designed, contrary to what the Minister said, to dilute the rights of data subjects where it should be strengthening them. For example, there is concern from the National AIDS Trust that permitting intragroup transmission of personal health data

“where that is necessary for internal administrative purposes”

could mean that HIV/AIDS status will be inadequately protected in workplace settings. Even on the Government’s own estimates it will have a minimal positive impact on compliance costs, and in our view it will simply lead to companies doing business in Europe having to comply with two sets of regulation. All this could lead to a lack of EU data adequacy.

The Bill is a dangerous distraction. Far from weakening data rights, as we move into the age of the internet of things and artificial intelligence, the Government should be working to increase public trust in data use and sharing by strengthening those rights. There should be a right to an explanation of automated systems, where AI is only one part of the final decision in certain circumstances—for instance, where policing, justice, health, or personal welfare or finance is concerned. We need new models of personal data controls, which were advocated by the Hall-Pesenti review as long ago

as 2017, especially through new data communities and institutions. We need an enhanced ability to exercise our right to data portability. We need a new offence of identity theft and more, not less, regulatory oversight over use of biometrics and biometric technologies.

One of the key concerns we all have as the economy becomes more and more digital is data and digital exclusion. Does DSIT have a strategy in this respect? In particular, as Citizens Advice said,

“consumers faced unprecedented hikes in their monthly mobile and broadband contract prices”

as a result of mid-contract price rises. When will the Government, Ofcom or the CMA ban these?

There are considerable concerns about digital exclusion, for example regarding the switchover of voice services from copper to fibre. It is being carried out before most consumers have been switched on to full fibre infra- structure and puts vulnerable customers at risk.

There are clearly great opportunities to use AI within the creative industries, but there are also challenges, big questions over authorship and intellectual property. Many artists feel threatened, and this was the root cause of the recent Hollywood writers’ and actors’ strike. What are the IPO and government doing, beyond their consultation on licensing in this area, to secure the necessary copyright and performing right reform to protect artists from synthetic versions?

I very much echo what the noble Baroness, Lady Jones, said about misinformation during elections. We have already seen two deepfakes related to senior Front-Bench Members—shadow spokespeople—in the Commons. It is concerning that those senior politicians appear powerless to stop this.

My noble friends will deal with the Media Bill. The Minister did not talk of the pressing need for skilling and upskilling in this context. A massive skills and upskilling agenda is needed, as well as much greater diversity and inclusion in the AI workforce. We should also be celebrating Maths Week England, which I am sure the Minister will do. I look forward to the three maiden speeches and to the Minister’s winding up.

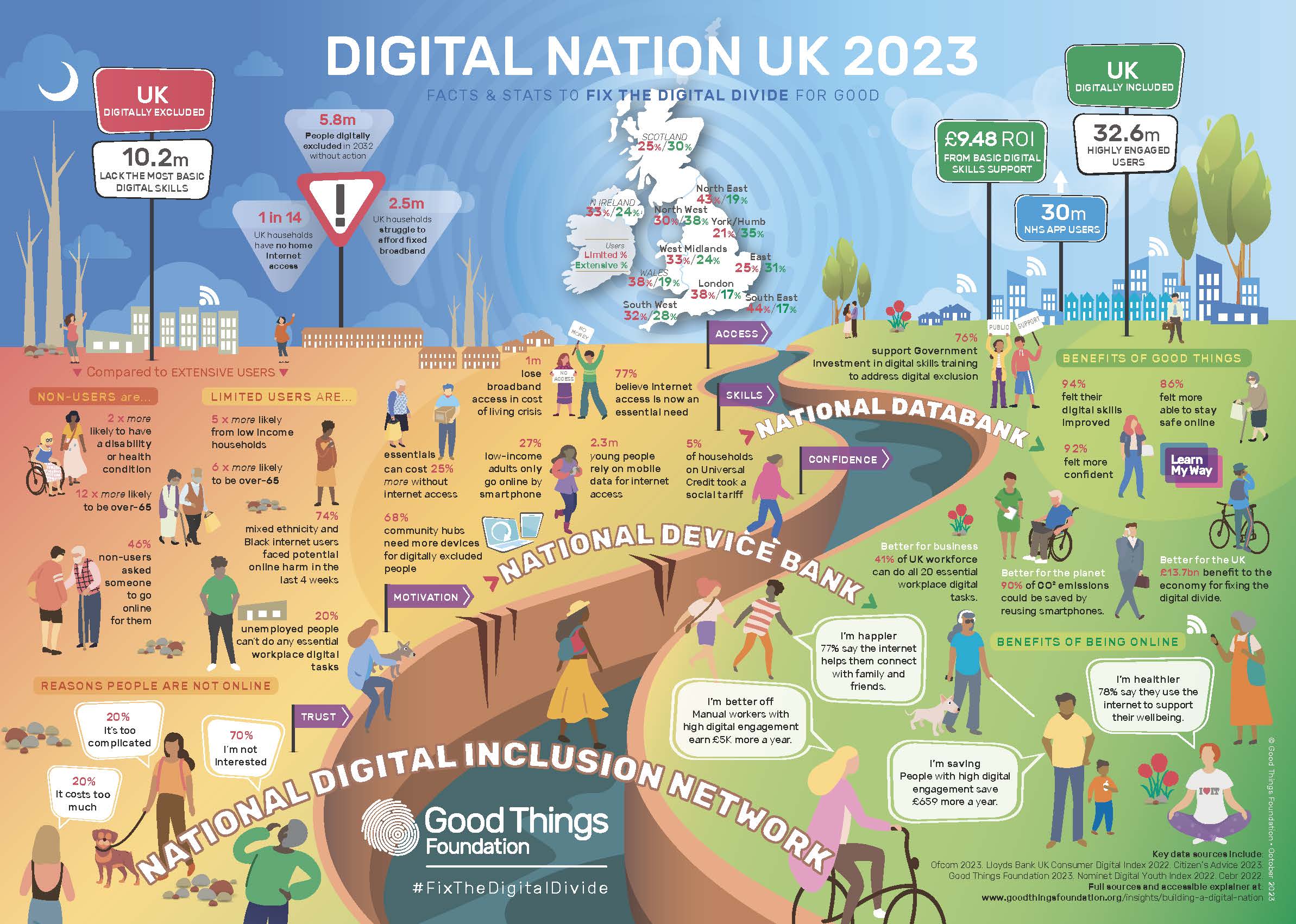

Lords call for action on Digital Exclusion

The House of Lords recently debated the Report of the Communication and Digital Committee on Digital exclusion . This is an editred version of what I said when winding up the debate.

Trying to catch up with digital developments is a never-ending process, and the theme of many noble Lords today has been that the sheer pace of change means we have to be a great deal more active in what we are doing in terms of digital inclusion than we are being currently.

Access to data and digital devices affects every aspect of our lives, including our ability to learn and work; to connect with online public services; to access necessary services, from banking, to healthcare; and to socialise and connect with the people we know and love. For those with digital access, particularly in terms of services, this has been hugely positive- as access to the full benefits of state and society has never been more flexible or convenient if you have the right skills and the right connection.

However, a great number of our citizens cannot get take advantage of these digital benefits. They lack access to devices and broadband, and mobile connectivity is a major source of data poverty and digital exclusion. This proved to be a major issue during the Covid pandemic. Of course the digital divide has not gone away subsequently—and it does not look as though it is going to any time soon.

There are new risks coming down the track, too, in the form of BT’s Digital Voice rollout. The Select Committee’s report highlighted the issues around digital exclusion. For example, it said that 1.7 million households had no broadband or mobile internet access in 2021; that 2.4 million adults were unable to complete a single basic task to get online; and that 5 million workers were likely to be acutely underskilled in basic skills by 2030. The Local Government Association’s report, The Role of Councils in Tackling Digital Exclusion, showed a very strong relationship between having fixed broadband and higher earnings and educational achievement, such as being able to work from home or for schoolwork.

To conflate two phrases that have been used today, this may be a Cinderella issue but “It’s the economy, stupid”. To borrow another phrase used by the noble Baroness, Lady Lane-Fox, we need to double down on what we are already doing. As the committee emphasised, we need an immediate improvement in government strategy and co-ordination. The Select Committee highlighted that the current digital inclusion strategy dates from 2014. They called for a new strategy, despite the Government’s reluctance. We need a new framework with national-level guidance, resources and tools that support local digital inclusion initiatives.

The current strategy seems to be bedevilled by the fact that responsibility spans several government departments. It is not clear who—if anyone—at ministerial and senior officer level has responsibility for co-ordinating the Government’s approach. Lord Foster mentioned accountability, and Lady Harding, talked about clarity around leadership. Whatever it is, we need it.

Of course, in its report, the committee stressed the need to work with local authorities. A number of noble Lords have talked today about regional action, local delivery, street-level initiatives: whatever it is, again, it needs to be at that level. As part of a properly resourced national strategy, city and county councils and community organisations need to have a key role.

The Government too should play a key role, in building inclusive digital local economies. However, it is clear that there is very little strategic guidance to local councils from central government around tackling digital exclusion. As the committee also stresses, there is a very important role for competition in broadband rollout, especially in terms of giving assurance that investors in alternative providers to the incumbents get the reassurance that their investment is going on to a level playing field. I very much hope that the Minister will affirm the Government’s commitment to those alternative providers in terms of the delivery of the infrastructure in the communications industry.

Is it not high time that we upgraded the universal service obligation? The committee devoted some attention to this and many of us have argued for this ever since it was put into statutory form. It is a wholly inadequate floor. We all welcome the introduction of social tariffs for broadband, but the question of take-up needs addressing. The take-up is desperately low at 5%. We need some form of social tariff and data voucher auto-enrolment. The DWP should work with internet service providers to create an auto-enrolment scheme that includes one or both products as part of its universal credit package. Also, of course, we should lift VAT, as the committee recommended, and Ofcom should be empowered to regulate how and where companies advertise their social tariffs.

We also need to make sure that consumers are not driven into digital exclusion by mid-contract price rises. I would very much appreciate hearing from the Minister on where we are with government and Ofcom action on this.

The committee rightly places emphasis on digital skills, which many noble Lords have talked about. These are especially important in the age of AI. We need to take action on digital literacy. The UK has a vast digital literacy skills and knowledge gap. I will not quote Full Fact’s research, but all of us are aware of the digital literacy issues. Broader digital literacy is crucial if we are to ensure that we are in the driving seat, in particular where AI is concerned. There is much good that technology can do, but we must ensure that we know who has power over our children and what values are in play when that power is exercised. This is vital for the future of our children, the proper functioning of our society and the maintenance of public trust. Since media literacy is so closely linked to digital literacy, it would be useful to hear from the Minister where Ofcom is in terms of its new duties under the Online Safety Act.

We need to go further in terms of entitlement to a broader digital citizenship. Here I commend an earlier report of the committee, Free For All? Freedom of Expression in the Digital Age. It recommended that digital citizenship should be a central part of the Government’s media literacy strategy, with proper funding. Digital education in schools should be embedded, covering both digital literacy and conduct online, aimed at promoting stability and inclusion and how that can be practised online. This should feature across subjects such as computing, PSHE and citizenship education, as recommended by the Royal Society for Public Health in its #StatusOfMind report as long ago as 2017.

Of course, we should always make sure that the Government provide an analogue alternative. We are talking about digital exclusion but, for those who are excluded and have the “fear factor”, we need to make sure and not assume that all services can be delivered digitally.

Finally, we cannot expect the Government to do it all. We need to draw on and augment our community resources; I am a particular fan of the work of the Good Things Foundation See their info graphic accompanying this) FutureDotNow, CILIP—the library and information association—and the Trussell Trust, and we have heard mention of the churches, which are really important elements of our local delivery. They need our support, and the Government’s, to carry on the brilliant work that they do.

Response to AI White paper falls short.

This is my reaction to the government's AI White Papert response which broadly follows the line taken by the White paper last year and does not take on board the widespread demand expressed during the consultation for regulatory action.

There is a gulf between the government’s hype about a bold and considered approach and leading in safe AI and reality. The fact is we are well behind the curve, responding at snails pace to fast moving technology. We are far from being bold leaders in AI . This is in contrast to the EU with its AI Act which is grappling with the here and now risks in a constructive way.

As the House of Lords Communication s and Digital Committee said in its recent report on Large Language Models there is evidence of regulatory capture by the big tech companies . The Government rather than regulating just keeps saying more research is needed in the face of clear current evidence of the risk of many uses and forms of AI. It’s all too early to think about tackling the risk in front of us. We are expected to wait until we have complete understanding and experience of the risks involved. Effectively we are being treated as guinea pigs to see what happens whilst the government taklks about the existential risks of AI instead

Further the response to the White Paper states that general purpose AI already presents considerable risks accross a range of sectors, so in effect admitting that a purely sectoral approach is not practical.

The Government has failed to move from principles to practice. Sticking to their piecemeal context specific approach approach they are not suggesting immediate regulation nor any new powers for sector regulators but, as anticipated, the setting up of a new central function (with the CDEI being subsumed into DSIT as the Responsible Technology Adoption Unit) and an AI Safety Institute to assess risk and advise on future regulation. In essence any action-without new powers- will be left to the existing regulators rather than any new horizontal duties being mandated.

Luckily others such as the EU-and even the US- contrary to many forecasts- are grasping the nettle.

My view is that

We need early risk based horizontal legislation across the sectors ensuring that standards for a proper risk management framework and impact assessment are imposed when AI systems are developed and adopted and consequences that flow when the system is assessed as high risk in terms of additional requirements to adopt standards of transparency and independent audit.

We shouldn’t just focus on existential long term risk or risk from Frontier AI, predictive AI is important too in terms of automated decision making. risk of bias and lack of traanspartency.